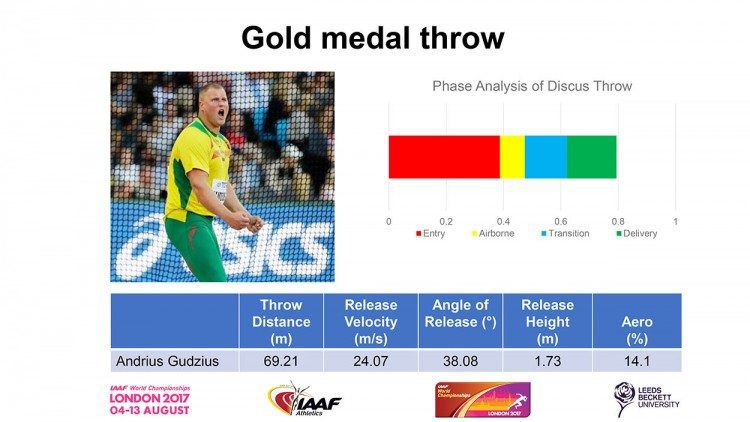

In the second part of our review of IAAF findings, we report on the biomechanical analysis of the men’s discus final at the London World Championships

Sport makes much of the concept of marginal gains, the aggregation of tiny improvements in overlooked areas that might provide the winning edge.

In winning the men’s discus at the IAAF World Championships in London by the narrowest distance in history – just two centimetres – it might be proposed that the Lithuanian, Andrius Gudzius, maximised his interpretation of the theory.

But what led to the narrowest of winning margins? Dr Athanassios Bissas, head of biomechanics at the Carnegie School of Sport at Leeds Beckett University, and his team of 40 scientists, were commissioned by the IAAF to study every scientific parameter of each throw in the men’s discus final.

Their detailed biomechanical analysis involved setting up three high-speed digital video cameras around the London Stadium to record data for 3D motion analysis at 150 frames per second.

According to Bissas, all three attempts by each athlete were recorded during the initial round and each attempt by the eight athletes during the final round was recorded for subsequent biomechanical analysis in the full findings which will be published by the IAAF next year.

For the preliminary findings shown here, only variables selected from the best attempts of the top four athletes – Gudzius, Daniel Stahl of Sweden, Mason Finley of the USA and Fedrick Dacres of Jamaica – during the competition were studied.

But they provide an insight into the technical elements of Gudzius’s victory.

Where medals were won

All of the medal-winning throws came in succession at the start of round two, with the lead changing hands in three consecutive throws.

Two of the top four in the competition set lifetime best performances with only Stahl, the eventual silver medallist, falling slightly short of his best.

What can we learn from the results?

There were distinct differences in technique among the leading throwers. Gudzius favoured a longer airborne phase and shorter delivery compared with Stahl, but clearly the performance outcomes were similar.

Where gold and silver medalists differed from other competitors was in their total throw duration. For Gudzius and Stahl, the throw duration (<800ms) was noticeably shorter than for the others. According to Bissas, it underpins the importance of explosive release in determining a successful throw.

Release velocity was also a significant factor with Gudziuz recording 24.07m/s compared with 23.97m/s by Stahl, 23.59m/s by Finley and 23.40m/s by Dacre.

It suggests that the development of release velocity should remain a primary focus of discus training and coaching.

THE STATE OF DISCUS THROWING – Q&A

Q. Has there generally been an evolution in discus technique?

A. No. Back in 1936 we had a side-on start, then came a backwards-facing run across, and we now have a wide right leg sweep run-across, generating as much momentum as is possible within the confines of the circle. We have reached a full stop.

Q. Is there still any place for these “older” techniques?

A. Yes, certainly with novices. The big danger is always in trying to impose advanced techniques on beginners. Once the novice has got beyond a standing throw, then the side-on technique is fine, because they are facing their line of direction and don’t have to cover the entire circle. Most decathletes simplify by adopting a technique in which wide leg sweep is modest, thus ensuring stability – and certain points.

Q. What about the throwing positions in London?

A. Here there were differences. Some throwers were seen to pin down both legs and hold them there, others to pin and take a step forward, others have a lesser left leg “block” and keep spinning over it. Perkovic pins at the front, then steps forward, while the German female throwers tend to hold both legs firm. Godzius drives right over the left leg and reverses. The Cuban athlete Caballero is what I would describe as a manic spinner, sometimes landing on both knees in the circle-centre. If she ever gets it right, we are looking at a throw in the mid-70m region, but just don’t hold your breath.

Q. What was the quality of competition?A

A. Very high. Perkovic dominated in the women’s event, with two throws over 69m and two over 70m. But the big surprise for me was the Australian Stevens, who went beyond her potential in throwing 69.64 to break a Commonwealth record that had stood for 22 years. The men’s event was as close as you can get, with Gudzius winning by a mere 2cm.

Q. Are there any lessons for British throwers?

A. Unlike countries like Germany and Sweden, we still have no real throwing culture. What we have is a postcode lottery, with isolated coaches like John Hillier beavering away without much support. And rugby union is now drawing from us big, strong men and women who might have become excellent throwers. This applies to the three heavy throws.

Q. What about the UK Sport Throws Initiative, bringing in champions from other sports?

A. That was an odd idea from the start. Had the money been invested in committed coaches then it might well have produced positive results. It is not just a matter of money, but one of professionals and volunteers working together. I had a great regional secretary Arthur Kendall, and he supported me in Britain’s first-ever junior decathlon initiative in 1964. I linked this up with my Five Star Scheme and by 1974 a host of international decathletes had appeared. This kind of initiative, linking coaching and competition, would still work.

The state of discus throwing Q&A by Tom McNab

» The discus preliminary report was jointly compiled by the following members of the biomechanics team from the Carnegie School of Sport at Leeds Beckett University: Dr Timothy Bennett; Dr Alexander Dinsdale; Dr Lysander Pollitt; Aaron Thomas; and Dr Athanassios Bissas

» Other analysis in this review series can be found here