World record-holders Gunder Hägg and Arne Andersson of Sweden and Sydney Wooderson of Britain all missed out on the Olympic glory they deserved mostly due to World War Two causing the cancellation of the 1940 and 1944 Games.

Hägg and Andersson would surely have fought for honours in the 1944 Olympics. Also, had they paced themselves better in their mile races, both were capable of breaking four minutes if they had run more evenly and hadn’t reached halfway in 1:56 in many of their attempts.

As for Wooderson, dubbed the Mighty Atom as he was 1.68m/5ft 6in and 56kg/123 pounds and resembled the famous comedian Arthur Askey, he was probably capable of an 800m or 1500m gold in 1936, a 1500m title in 1940, a 5000m win in 1944 and a 10,000m gold in 1948.

While his fellow world mile record-setter Steve Ovett can also boast an English National junior cross-country title, an Olympic 800m win and a Commonwealth 5000m title, only Wooderson has achieved a world 800m record, a European 5000m victory and a 10-mile National senior cross-country title.

Wooderson may have had a hard task against a brilliant Jack Lovelock in the Berlin Olympics – the Kiwi had beaten him into second in the 1934 Empire Games – but in my view he certainly wouldn’t have done worse than second if fully fit in those Games.

The Briton had been one of the favourites for 1936 glory having beaten Lovelock in the AAA Mile in front of a 50,000 crowd at White City in July and he had also beaten him in the 1935 AAA Mile too. However, a few days before the Olympics he had turned his ankle badly (later revealed as a breakage) and he dropped out of his heat in Berlin.

Once recovered in 1937, he set a world mile record of 4:06.4 at Motspur Park in August and then in August 1938 at the same venue the Blackheath Harrier broke both the 800m and 880 yards records with times of 1:48.4 and 1:49.2.

The following month he easily won the European 1500m title in Paris in 3:53.6 although he had to miss the earlier Empire Games in Sydney to take his law exams.

In 1939 he won the AAA mile for the fifth consecutive year in 4:11.8 with a 27.9 last 200m, but because of World War Two there would be not be another AAA Championships for seven years.

Wooderson’s poor eyesight kept him from active duty in the war although he was a firefighter during the Blitz and was in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers as a radar operator. During the war his running ticked over with his annual best mile times between 1940 and 1944 being 4:11.0, 4:11.2, 4:16.4, 4:11.2 and 4:12.8.

Not long after the latter race in June 1944, he suffered severe rheumatic trouble and was in hospital for four months and his doctor said he must give up any hope of running in the future. After a two months of convalescence, though, he began to jog but a return to top class racing looked impossible but he would shock the athletics world with one of the greatest ever comebacks.

Meanwhile, further afield, it’s worth noting that in the war years athletics fans eyes were on neutral Sweden and Hägg had broken Wooderson’s mile record of 4:06.4 with 4:06.2 in 1942 but it had fallen to 4:02.6 just a year later to Andersson. Hägg had also become the first athlete to break 14 minutes for 5000m in 1942, a year he also just missed becoming the first man to break eight minutes for 3000m with 8:01.2 which was a world record by eight seconds.

In 1944 it would prove to be an even more cracking season for mile aficionados as the Swedish pair targeted more record breaking. Hägg set a two-mile world record of Oestersund in June of 8:46.4. Three days later in a tactical 1500m, Andersson outkicked Hägg with a 43.1 last 300m to beat his rival by 10 metres in 3:48.8 – almost four seconds down on his world record.

In July, Andersson who had been working on his speed, obliterated the three-quarters mile best with a stunning 2:56.6 with a 57.4 last lap at Stockholm. Two days later he took on Hägg at 1500m in Gothenburg.

The early pace was sensational with Lennart Strand, who was a future 1500m world record breaker himself, blasting through 400m in 56.7 and 800m in an unparalleled 1:56.5. Hägg, who’d been following closely, took over with Andersson, who’d held back a little, four metres back but closing.

At 1200m in 2:58.0, Andersson was on Hägg's heels but he was a spent force, possibly not helped by his run a few days earlier, and Hägg went away to win in 3:43.0. That took two whole seconds off his rival’s mark with a well-beaten Andersson still running a second faster than his previous record with 3:44.0. A week later Andersson outsprinted Hägg in another slow race 3:48.4 to 3:49.2.

Four days later they clashed in a mile with a capacity 14,000 crowd at Malmo on a 393m track. Strand, who was to win the 1948 Olympic 1500m silver medal, again set a fast early pace of 56.8 and 1:56.0 just ahead of Hägg with Andersson much closer this time.

The pace slowed as Hägg took over and he looked tired as he led through 1200m in 2:58.5.

Hägg tried to lift the tempo but Andersson was right beside him and as they went through 1500m in 3:46.0, the latter was much the stronger and he kicked away to win by three metres in 4:01.6 to take a second off his record with Hägg's 4:02.0 also inside the mark and well under his previous best of 4:03.6.

Andersson continued his dominance over Hägg, beating him in the Swedish Championships at Stockholm in August in 3:49.6 to 3:50.0, then a 2000m 5:12.6 to 5:13.2 and then a 2 miles 8:20.8 to 8:22.4. Overall in 1944 Andersson won the rivalry 6-1 but over their careers it was still Hägg dominating 14-7.

At the beginning of 1945, Hägg went on tour in the USA but after catching flu he ran badly but by July he was training well with Strand and he looked forward to taking on Andersson in Malmo on July 17 with again a sell-out crowd of 14,000.

Hägg's team-mate Ake Pettersson set another fast pace with 56.5 at 440 yards but he slowed to 1:59.2 at halfway. Hägg then took over and lifted the pace and passed three-quarters of a mile in 3:01.4. He kept the pressure up to pass 1500m in the fastest ever mile split time of 3:45.4 with Andersson trailing by a few metres in 3:45.8.

The latter though kicked up to Hägg's shoulder in the straight and 50 metres out they were level but Andersson was at his limits and Hägg pulled away again to win by six metres in a world record 4:01.3 with a tired Andersson timed at 4:02.2.

Andersson’s next big race was at White City on August 6 1945 on August Bank Holiday, a month before the war officially ended.

His opponent was Wooderson who eight months after his convalescence now thought he was ready to race Andersson himself, though few thought it was going to be close given one runner had a recent 4:02 PB and the other 4:06 from eight years ago and had been very ill a few months earlier.

The event organised by the AAA invited both Hägg and Andersson and after being starved of top class sport during the war a capacity 52,000 crowd was attracted (including a 16-year-old Roger Bannister) and a locked gate being charged down resulted in an extra 7000 gaining free entrance.

Wooderson, with his receding hairline and frail, pale and gaunt physique, looked a lot older than his 30 years, was up against the relatively muscular and athletic Swede.

After a fast 2:02 at halfway, Wooderson pushed on to lead at three-quarters of a mile and the crowd roared as he fought hard on the last lap with Andersson predictably winning but having to work far harder than anyone imagined in 4:08.8 to 4:09.2, great times on the notoriously slow track.

Six days later future European champion Strand beat Andersson in the Swedish Championships 3:47.6 to 3:49.6 and also in a smaller meet at 1500m but Andersson was up for a mile race on September 9 which attracted a record 20,000 crowd to Gothenburg to see a rematch between the two previous mile record-holders.

A pacer took them through 400m in 58.5 and then Andersson pushed on through 800m in 1:59.5. He was through 1200m in 3:02 but surprisingly Wooderson hung on and even though it was far in excess of any previous pace he had attempted, 220 yards out, Wooderson shot by and powered past 1500m in 3:48.4, which was not only a PB but a British record.

Andersson had to fight all the way and kicked by to win by a few metres in 4:03.8 from Wooderson’s 4:04.2. Not only was it a two-second PB and British and Commonwealth record it moved him to fourth all-time behind the three Swedes from the Malmo race (Rune Persson ran 4:03.8). Wooderson's lap times were 59.0, 61.5, 62.5 and 61.2.

Hägg won the two miles in London and then took on Andersson in Stockholm on September 21 but both were well beaten by Strand who won in 4:04.8 to Andersson’s 4:07.2 with Hägg fourth in 4:12.2.

In October the Swedish federation announced after an investigation into expenses they were suspending Hägg and Andersson and the pair never raced seriously again. Hägg's mile record would last nine years until Bannister’s historic 3:59.4 in 1954.

His 1500m record lasted a similar time though Strand equalled it in 1947 as did German Werner Lueg in 1952. Bannister also unofficially equalled it during his mile record but it finally officially fell when Wes Santee was timed at 3:42.8 in June 1954 during a 4:00.6 mile where he faded in the final straight.

Despite breaking new ground in his mile, Wooderson decided to move up in distance and won the 1946 AAA three miles title in a British record 13:53.2 with a 58 last lap.

He then won the European 5000m title in Oslo with ease by five seconds with another fast finish. His time of 14:08.6 was an astonishing 23 seconds inside the British record and the second fastest in history. The well-beaten Emil Zatopek in fifth and Gaston Reiff in sixth would go on to win Olympic titles.

His last track race, not long after the 5000m victory was a two miles race in which he had originally hoped to attack the world record. The race, like his AAA three miles win and European title are well worth a watch on YouTube.

He looked majestic after a mile as the excited crowd yelled their encouragement and he had a big lead. However, his Achilles began to tighten and he was limping very badly over the last few laps. He carried on, not wanting to drop out as there was a team competition and he still won in a fast time but it almost certainly cost him a record.

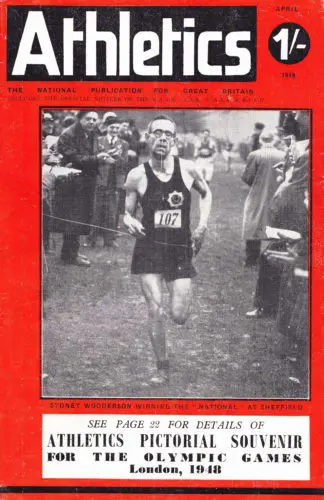

He announced his international retirement in 1947 but was still in tremendous shape and wanting to support his beloved Blackheath Harriers that during the 1948 winter he won both the Southern and National Cross-Country Championships over 10 miles.

Now it seems strange that Wooderson retired so close to the London Olympics while in such sensational form having beaten the likes of Zatopek and Reiff in 1946. It’s worth noting in London 1948 he would have been a similar age to Mo Farah was when retaining his Olympic 5000m and 10,000m crown in Rio and, because of the war, Wooderson had had a very light racing programme between 1940 and 1945 but back then there was no financial incentive to carry on running and track athletics was considered a young man’s sport.

As easily the country’s most popular and best-known athlete, many thought though as he was not competing, he would be a natural choice to light the torch at the Opening Ceremony and he was advised that he would be selected. However, reportedly the organisers decided they wanted someone who looked more 'athletic' and so the statuesque 400m runner John Mark was chosen instead.

The late Commander Bill Collins, who organised the 1948 Olympic torch relay, is on record that "such was the then organising committee’s obsession with a handsome final runner to light the Olympic flame that even the then Queen remarked to me ‘of course we couldn’t have had poor little Sydney'."

While not considered suitable for that role, he did at least become the Blackheath Harrier President in 1946 and the Centenary President in 1969 and he carried on attending club events.

One of his last competitive outings was for Blackheath in the 100 x one-mile relay in Crystal Palace in the 1970s. He was awarded an MBE in the 2000 Birthday Honours for services to Blackheath Harriers and athletics and died aged 92 in 2006.

» For more on the latest athletics news, athletics events coverage and athletics updates, check out the AW homepage and our social media channels on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram