Australian icon talks about embracing the pressure and unwittingly becoming the symbol for something far bigger than sport.

September 25, 2000. “Magic Monday”. Mythical might actually be a better word for it. Certainly, there was something otherworldly about what was happening on the track for 49.11 seconds of that evening, with Stadium Australia bursting at the seams. The capacity crowd of 112,524 were entranced, while the woman they were all watching found herself entering another dimension.

The video evidence proves otherwise but, even 25 years on, Cathy Freeman maintains that she didn’t feel her feet touch the ground for the closing 80m of the Olympic women’s 400m final in Sydney.

“I was being carried,” she says. “It just sounds so odd, doesn't it?”

Odd, perhaps, but also in-keeping with a sporting moment that has more than stood the test of time. That race brought Australia to a standstill, becoming one of those rare “where were you when?” occasions. Just last year, it topped a poll by The Guardian to find Australia’s greatest sporting moment, while the estimated TV audience of 8.8 million – this was before the current ratings system was established – stood as the nation’s biggest until 2023, when it was overtaken by the women’s World Cup semi-final between The Matildas and England.

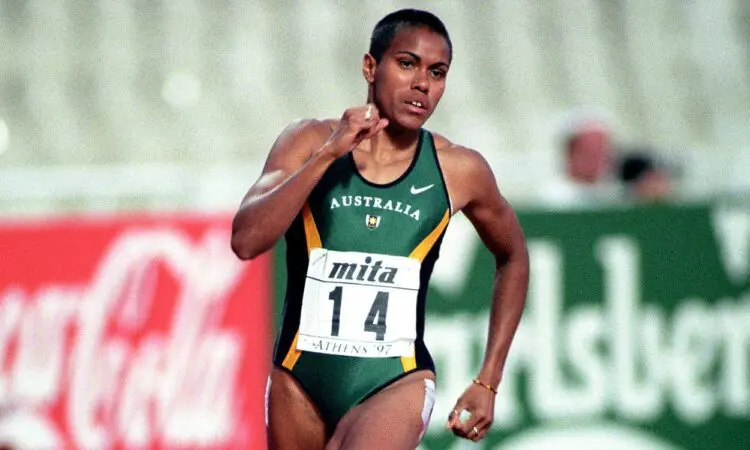

And the whole thing rested on one person. Freeman, then 27, had won two world titles in a row – in 1997 and 1999 – but the top Olympic prize had thus far been elusive.

Her athletic talent had been clear from an early stage and she was just 16 when she became the first indigenous Australian to win Commonwealth gold, in the 4x100m, in 1990. Her big individual breakthrough came, however, when she won Commonwealth 200m and 400m gold in 1994. One year previously, it had been announced that Sydney would host the 2000 Olympics. The path was set for a victory that would ultimately be about so much more than sport.

After every one of her major victories, the now 52-year-old who describes herself as: “A dirt and wood girl who grew up in the outback of Queensland and Bush regions of Australia,” flew the aboriginal flag. At first, it was seen as a controversial move – Australia’s chef de mission in 1994 even tried to stop her from doing it – but, by the time she stood at the foot of a precipitous staircase, about to light the Olympic flame in Sydney, Freeman had become the public symbol of reconciliation in her country.

The process of improving relations between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians had long been on the agenda but it had never been more prominent than in 2000. May of that year had seen the “Walk for reconciliation” across Sydney Harbour Bridge, the largest political demonstration in Australia's history at the time.

Before she had even run a step, Freeman’s very presence at that opening ceremony was hugely symbolic.

She might have prepared for the Games in England, under coach Peter Fortune and alongside fellow Olympic finalist Donna Fraser, but in the host city her image, her presence, was everywhere.

“The glare,” she says, speaking to AW from her Melbourne home, when asked what immediately comes to mind when she thinks back to those Games. “The theatre of it all, the spectacle, what it meant to people and how people still connect with those Games. The strength of that connection to those Games is just unflappable. People are just still so attached and so connected to that time.”

Freeman had a strong support group but, looking back at the footage and the images, it’s striking how often she seemed to be entirely on her own. For the vast majority of people, just being able to function under that kind of pressure and attention would be an achievement in itself but there was a seeming effortlessness to how she navigated through it all. The key, she says, was keeping it simple.

“The enormity of it could have so easily overwhelmed me, and the sentimental aspect of it, to Australians, particularly to the First Nations community of Australia,” she says. “I was just moving through with a very simple approach to everything – to do what we'd always done and treated each day as no different to the day before in terms of attitude, mindset, approach, philosophies. We knew that the big occasion would somehow pull out of me as a competitor what I needed to release in terms of my competitiveness.

“I learned and honed a way of moving through it all so that I was able to maintain my feeling of joy and freedom that I felt when I raced and when I ran. I was determined to live my life exactly how I wanted to live it and that was really clear, I feel. And it showed.”

Before she could embrace the familiarity of competing on the track, though, her ceremonial duties needed to be completed – no easy task in themselves. When Freeman took the torch from 1998 Olympic 400m hurdler Debbie Flintoff-King at the opening ceremony, she had what now seems like a faintly ludicrous number of steps to run up, before then essentially lighting a ring of fire around herself that would rise above her, looking a little too close for comfort. It’s hard to imagine it passing the health and safety checks of today.

With her job seemingly done, Freeman stepped away, expecting to see the “cauldron” ascending to its place at the top of the stadium. With 3 billion people watching, however, it failed to launch. For four long minutes, Freeman remained the consummate professional, holding her torch aloft until the problem was fixed.

“I feel a little bit unwell thinking about those moments, because it was quite intense,” she laughs now. “The numbers when you look at the viewership all around the world and in Australia are just mind boggling. It's only now I sit and I ponder those numbers and think: ‘Oh my goodness’.

“Because I was so focused, I kind of compartmentalised lighting the flame at the opening ceremony. I kept it separate from the focus and that part of my life and my mind where I was there to race and I was there to compete to the best of my ability.

“It was absolutely an amazing honor but nobody can really prepare you for that kind of amazing responsibility. Folks often say: ‘Did it make you feel like you were under any more pressure?’, as if I wasn't under enough expectation already? But I think competitors have this silent but deadly self belief that I held sacred.

“I knew how to protect my inner sanctity and I think it also helped that my two training partners (Freeman also trained with Australian runner Sean McLoughlin), when I found out that I was lighting the cauldron, were very much across what lay ahead of me, and I think that helped me cope as well.

“In rehearsal, the day of the opening ceremony, everything was perfect, but when it came to the actual night of the opening ceremony, it's now public knowledge that the cauldron broke down and malfunctioned for four minutes. I thought it was far less than that but, gee whizz, the fact that it broke down…it’s still hard to wrap my head around that it even occurred. It could have so easily become a bit of a true disaster.”

A more comforting memory comes from recalling the crowd’s reaction to her first accepting the torch. The film clearly shows Freeman being somewhat taken aback by the wave of affection being sent in her direction.

“I had a sense for how people were going to react – not entirely, but I allowed myself to think about it at times,” she says. “I knew that once I got on the track and started racing, that would be where I felt in my element at my most natural. But certainly the reaction when Debbie Flintoff-King gave me the flame certainly was really quite beautiful. The reaction I felt was lovely. I haven't really thought about it before, so thank you for asking, but it was warm and sincere. I was feeling very, very honoured indeed.”

But, still, there were 10 days between that moment and the race that would define her sporting life. 10 days for the story to grow and the pressure to build. Sydney was Freeman’s third Olympics. Four years previously, in Atlanta, she had been beaten to silver by Marie-José Pérec and the French two-time champion was not only seen as the biggest threat but the foe that the Australian favourite was desperate to face once again.

The rematch was not to be. Claiming to have been threatened and harassed by the Australian media and public, whom she felt were trying to sabotage her chances, Pérec withdrew less than 48 hours before the opening heat, fleeing the country.

“My heart dropped when I heard the news,” says Freeman. “I was quietly devastated, because I knew that I needed her. I needed to race against her to feel this sense of satisfaction at even having a shot at winning against her in my home country.

“But, at the same time, I respected her decision. I remember thinking to myself: ‘Geez, she really must be so confident in the decision that she's made’. Selfishly, it was a heart-dropping moment but, on the other hand, I had to accept it, and I respected her wishes.”

The removal of that showdown might have made the route to gold that bit easier for Freeman, who also finished sixth in the 200m final in Sydney, but now she was fully expected to win it.

“I was very clear on what I needed to do, and I held on to my coach’s every word, because it can often just make you feel safe – knowing what the instructions were and the steps I needed to take,” she says. “The first and second rounds are often just a case of not being too complacent or overconfident, but feeling strong and relaxed. The semi-final is where the intensity has to increase, and you almost have to treat it like a final, because surprises happen all the time. You have to be quite assertive and very commanding in your presence as a contender for the gold medal, so I made sure I did that. I made sure that the other girls were going to have to compete against me.”

And so came the final, where a striking surprise was sprung by Freeman, who lined up in a full body Nike “swift suit”, complete with hood. Surely something so claustrophobic had the potential to be more of a hindrance than a help?

“I had those very same questions when I was presented with the idea and the whole concept,” she says. “[Designer] Ed Harber was a driving force behind the research and design of it, and we sat down and got into it and discussed it. I trialled it in a 200m race in Gateshead and I got used to the new pre-race ritual.

“I was hesitant because I thought: ‘I'm already going to be given enough attention. I don't need to add to the drama’. But, to be really truthful, it made me feel really good. As soon as the gun went off, I forgot I was even wearing it. I remember actually feeling like I was slicing through the air and it felt beautiful, it felt really good. I would not have worn it if I hadn’t felt good in it.”

There are two aspects to the race itself that Freeman recalls particularly clearly. The first was that she didn’t feel like she was being tested.

“We all knew that I had every advantage under the sun and I remember the girls, even with 110, 120m to go, nobody forged their assertiveness in terms of: ‘I can win this’. Nobody really pushed it.”

As the field came off the final bend, Freeman, Lorraine Graham of Jamaica and Britain’s Katharine Merry were shoulder to shoulder but it was there that the Australian strode out.

“You can see that I don't really make a move until we're well into the home straight because you just can sense, energetically, nobody believes that they can win this thing,” adds Freeman. “If Marie-José Pérec had been in the race, in top form, the tactics of the race would have been completely different. It would have been far more intense from the moment the gun went.”

It was also, at that point, where the leader had that sensation of losing touch with terra firma.

“It literally felt like my feet weren't touching the ground and I was being carried,” she adds. “It just seemed like everybody was gunning for me to win this thing and it was just so surreal to not feel your feet touch the ground. It’s one of the most bizarre set of circumstances.”

That sensation is one of the reasons why, as soon as she came through the line, Freeman not only sat down, but removed her shoes.

“I spent a lot of my childhood barefoot,” she says. “I think I needed to just feel the ground under my feet, to feel grounded because there was absolute…I wouldn’t call it pandemonium but there was some magic emotion happening around me. It was extraordinary.”

There were some mixed emotions, too.

“I remember, I was mid-air, and I thought: ‘So this is what it feels like to be an Olympic champion’,” says Freeman. “And then I remember looking at the time and being disappointed. I was really, really hoping to get under 49 seconds (Freeman’s PB is 48.63), and I didn't. I ran 49.11 and for a quarter miler, running 48 seconds, it's exceptional. It's a special result.

“I cherish my Olympic gold medal but there's always this thing about not running 48 seconds. It’s an itch I cannot scratch or it's an itch that will always need scratching. It's the strangest sensation.

“I just would have loved to have run faster that night. There's a part of me that [thinks] could have, would have, should have, but, at the end of the day, winning an Olympic gold medal is the pinnacle in track and field.”

This is not to say that happiness escaped the victor. Far from it. It did take a while after the end of the race before the first smile broke across her face, but she beamed for the rest of the night. As she completed her lap of honour, Freeman did so carrying both the Australian and Aboriginal flags – further cementing that sense of unity. The move wasn’t entirely without controversy, though. The IOC did not recognise the Aboriginal flag but the then Prime Minister went so far as to send a telegram supporting Freeman’s actions.

“I was just so drowning in celebration, of feeling so personally satisfied and just so happy that I'd gotten through everything in one piece, that I just didn't give much thought to the naysayers or those who didn't quite understand or connect to why I flew both Australian flags,” she says. “I've come to accept that you can't be understood by everybody.

Not everyone's going to embrace each other in the true spirit of solidarity. I'd always flown both flags in any major title I've ever won so it really shouldn't have been a surprise, especially to track and field fans or people who followed my story.”

And it undoubtedly made an impact. Freeman retired from athletics in 2003 and, four years later, founded the Cathy Freeman Foundation – now called Murrup – to help with schooling for Indigenous Australian children. It’s that lap of the track, though, which remains the biggest reference point.

“I've been told many things – and by my fellow First Nations community members or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members – that I have left breadcrumbs for others to follow,” she says. “But I was not really planning to create what seems to be a lasting impact. I was just always about personal expression and pride in who I was as an Australian Indigenous girl. It was more about me sharing all of me with the world. But, certainly after all these years, it makes me really proud.

“You can go to some of Australia's most notable tourist sites or landmarks, in the cities and in the rural parts of Australia, and communities are proud to fly the Aboriginal flag. They proudly embrace the ancient culture of indigenous folk here in Australia and it's nice that I helped to create a platform, aided in the cause of being more visible or gave voice, or however you want to put it, I certainly unwittingly created this impact and that's the only way I can really respond.”

That the story still resonates is a gift that Freeman doesn’t tire of receiving.

“Anyone who was in the stadium that night will often share with me how they still get shivers when they reflect,” she says. “From my point of view, it’s a vastly different story but it's one of these moments where there really was true unity playing out. It was just so beautiful to be a part of and to see it in front of my very own eyes.”

Does it still give her shivers?

“It absolutely takes my breath away.”

“I wonder if we’ll ever get a moment of that magnitude again”

Katharine Merry, 400m bronze medallist at Sydney 2000, shares her memories of that final

One of the best things Cathy did was to embrace everything. You think of Super Saturday at London 2012 with Mo Farah, Jess Ennis-Hill and Greg Rutherford. They all had pressure on them – perhaps less so with Greg – but they shared that pressure and expectation on that one night, whereas Cathy had nobody to share that with. It was huge.

The call room was quiet and no-one was looking at each other. Everyone knew what this race was about and it gradually got bigger and bigger in terms of expectation and volume as we walked in single file, in lane order, into the stadium.

It's like somebody was turning up the volume as we were walking closer and closer to the track, under the seats and then coming out into the arena. It was absolutely deafening when we walked in. I’ve never heard a sound like it and I never will again.

There was no pressure on anybody else. It was Cathy's to lose. A few of us thought: “We could have a pop here” and I tried to win it. I wanted to fly out with people throwing eggs at me, being that person that absolutely pooped the party.

We walked around to the first bend, taking it all in, and I saw my coach, Linford Christie, in the crowd. He lost a very expensive bracelet that night because it flew off when he got too excited. He never got it back. It’s funny the things you remember.

The starter got us on the blocks and it went really quiet. You could have heard a pin drop. I don't remember the gun going, I don’t remember the first bend, but I do remember the back straight vividly, because that was just all cameras, bulbs, lights, which I hadn't catered for. That took my attention for a little bit.

Most of the back end of the race was in slow motion and I remember it in slow motion, because it was so bloody painful. That's when the wheels started falling off, and it was just gritting my teeth and thinking: ‘Don't let anyone else past me’.

There were three of us pretty much in a line coming off the final bend and then Cathy pulled away. Lorraine Graham pulled away a little bit too and I realised: ‘I’m third here, I can’t see anyone else’, but the line just wasn’t coming because I was dying. Remember, we’d had four rounds in four days.

Cathy wasn’t happy with the time she ran and she doesn’t feel that anybody took the challenge to her, but I don’t agree with that – we just weren’t good enough. She was just better than us.

And it’s a moment that’s stood the test of time. I was in a taxi in Australia during the Gold Coast Commonwealth Games in 2018 and the driver found out that I’d come third in the final. He said: “I remember that night". I was driving my taxi and the road were gridlocked and I was thinking: ‘I’m going to miss it. I'm going miss it. I need to see this race’. He pulled up to a random person's house, ran and knocked on the door, and everyone was just inviting everybody in to watch it on the TV.

Nobody wanted to miss it. I wonder if we'll ever get a moment of that magnitude again.