Research shows that the menstrual cycle has a potentially negative impact on female athletics performance. Georgie Bruinvels reports on her latest study

Many women athletes say their menstrual cycle impacts upon their training and performance. Last year British tennis player Heather Watson made headlines around the world when she attributed her Australian Open loss to her period, finally breaking silence on what has become one of the biggest taboos in sport. Yet precisely why elite performance often – but not always – suffers is not yet clear. That is part of the reason why my own research group – a collaboration between UCL and St Mary’s University and supported by Orreco – is aiming to shed more light on this area.

As scientists, what we do know is that heavy menstrual bleeding raises the risk of a woman losing excessive amounts of iron, present in blood, on a monthly basis. Iron is an essential micronutrient vital for metabolic and physiological function. If iron deficiency is left untreated, it might progress to iron deficiency anaemia. This is where oxygen transport is compromised among other factors, which will cause fatigue and negatively affect health and performance.

However, even in top athletes, awareness of the link between menstruation and iron deficiency is poor. Latest evidence suggests that around half of exercising females may have a compromised iron status. As previously reported in AW, numerous other factors such as sweating and foot-strike haemolysis, can cause athletes to experience small iron losses while training, increasing their susceptibility to a low iron status.

However, the impact of iron deficiency and the criteria used to define it are ambiguous. The prevalence of iron deficiency is greater in female athletes, likely due to the menstrual cycle, and this risk is more pronounced in those who have heavy menstrual bleeding. Our research has revealed heavy bleeding to be common in marathon runners, affecting more than one third (36%), and, perhaps surprisingly, this was equally as common in elite level athletes (37%).

The female athlete triad and the newly termed “relative energy deficiency in sport syndrome” (RED-S), which are associated with amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea – are more common areas of study, but we have highlighted that investigations into other menstrual cycle irregularities are also necessary. Our studies are among the first to investigate the many ways in which menstruation might affect competition and training.

It’s hugely important to explore any links. In the past, research trials were conducted only on men, partly because the variations in reproductive hormones that occur through the female menstrual cycle mean that conducting research in females is more complex and expensive. As a result, the ‘taboo’ subject was either ignored entirely, or women were targeted for participation in studies only during the early follicular phase of their cycle, when hormone levels are at their lowest. Some researchers recruited women only if they were taking the oral contraceptive, therefore enabling more control and standardisation of the reproductive hormones.

But as sports science has advanced, so it has become evident that there are gender-specific influences on performance. Since women compete during all phases of their menstrual cycle, a huge area of necessary research has been missed by failing to recruit female participants in trials, something we highlighted recently in an editorial in the British Journal of Sports Medicine. We are hoping to change that and recently organised a trial to look specifically at the impact of both the menstrual cycle and low iron levels on exercise capacity, quality of life and mood.

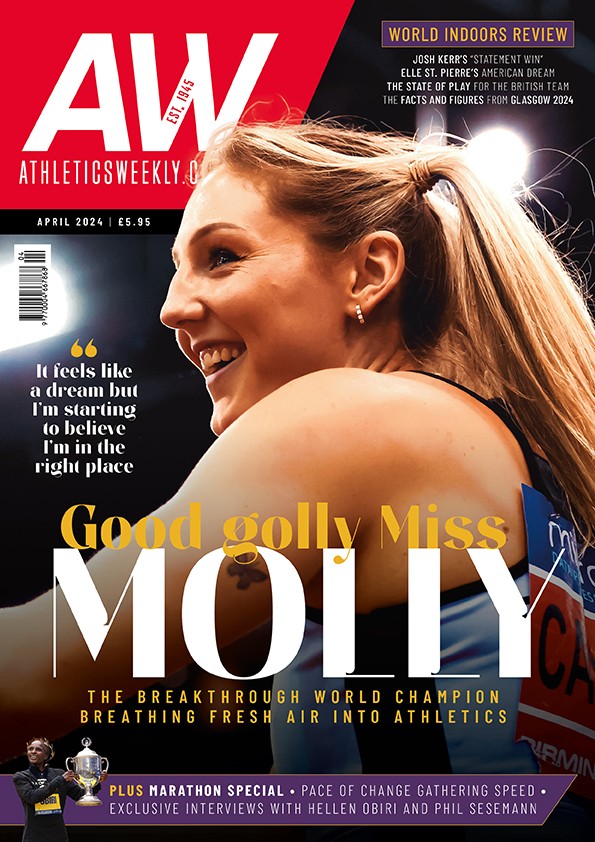

» Georgie Bruinvels (pictured above) is a member of Aldershot, Farnham & District AC and a GB international. She is a researcher at St Mary’s and UCL’s Division of Surgery and Interventional Science

A PERFORMANCE CURSE?

What is the menstrual cycle and what do we already know about its effects on an athlete’s body? Peta Bee reports

It is dubbed ‘the curse’ and is indeed the scourge of many women’s lives, with the hormonal flux of the monthly menstrual cycle being blamed for everything from mood swings to over-eating. But what is really going on? There are distinct phases of a 28-day menstrual cycle: the first is menstruation, which lasts 4-5 days and in which levels of the hormones oestrogen and progesterone levels are both low.

In the second (follicular) phase, oestrogen levels peak before dropping slightly during the third (early luteal) phase when progesterone levels rise. In the late luteal phase towards the end of the cycle, both oestrogen and progesterone levels drop rapidly before menstruation begins again. For some female athletes, hormonal roller-coaster of the cycle affects quality and quantity of training as well as predisposing them to a higher risk of injury.

Stomach cramping is the leading complaint, but South African studies have shown that that this variation in hormones throughout the typical cycle can influence exercise performance in subtle ways, such as changing the body’s temperature regulation and influencing how it processes carbohydrates, protein and fat.

Jessica Judd has described how her own times can vary by up to 15 seconds depending on the stage of her menstrual cycle. “It’s scary that it can affect you so much because it’s the difference between first and last,” Judd said last year. Time it correctly, however, and the menstrual cycle might act in your favour.

In a study on cyclists asked to perform a time trial, exercise scientists at the University of Cape Town and the Sport Science Institute of South Africa found that competing one to two days before ovulation, when oestrogen is highest and progesterone is lowest, may enhance endurance performance.

Of course, not every woman is affected in the same way. In an interview with the BBC last year, Paula Radcliffe described how she tried taking the drug norethisterone, a synthetic progesterone, to delay menstruation when her period was going to interfere with a competition, but discovered that it “made things a hundred times worse”. When her period started just before she took part in the 2002 Chicago Marathon, Radcliffe says she took nothing. “I broke the world record so it can’t be that much of a hindrance,” Radcliffe said. “But undoubtedly that’s why I had a cramped stomach in the final third of the race and didn’t feel as comfortable as I could have done.”

How else it might affect your training?

Joints: Women athletes are up to eight times more likely to suffer knee problems than men, partly because the wider angle of their hips puts added stress on the knees when training, but also because hormones such as oestrogen weaken ligaments at different phases of the menstrual cycle, leaving them prone to twisting or straining. Researchers at the University of Calgary revealed that the timing of hormone- induced laxity – or flexibility – of joints varies among women, with most experiencing some pain or discomfort around ovulation, but others displaying a greater predisposition to knee and joint problems at the very start or end of their cycle.

Stomach: Painful menstrual cramps (called dysmenorrhea) are among the most common pre-menstrual symptoms and the one most likely to deter women from training. During the menstrual cycle, the lining of the utereus produces a hormone called prostaglandin that causes the uterus to contract, often painfully. Women with severe cramps may produce higher-than-normal amounts of prostaglandin.

Sleep rhythms: Researchers at the University of California found that 67% of women who menstruate have difficulty sleeping for two or three days during every cycle. Premenstrual insomnia seems to be associated with a rapid drop in the hormone progesterone. “Progesterone is a soporific, a sedative-type drug that your body gives you every month when you ovulate,” says Dr Kathryn Lee, a sleep researcher who carried out the Californian study.

Appetite: A drop in serotonin levels usually occurs just prior to menstruation. Since the body uses carbohydrates to make seretonin, it can trigger an urge to eat more carbohydrate foods. According to Pamela Peeke, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore who has researched the effects of the menstrual cycle on appetite, many women grab sweet, high-carb treats because simple sugars are metabolised more quickly, offering a quick serotonin fix.