US athlete made his mark in a way no distance runner had done before or since and 50 years after his death we look into what made the ‘James Dean of athletics’ such a phenomenon

“I thought you might ask me that,” says Linda Prefontaine, a knowing laugh transmitting its way down the phone line. We are talking about her late brother and the question to which she is referring is one that has been posed repeatedly for decades now: just what is it about Steve Prefontaine that has left such a lasting impression?

May 30 will mark 50 years since America’s front-running, moustachioed all-action athletics hero lost his life after crashing his butterscotch-coloured MG sports car – bought with his first paycheque from what would become the sporting behemoth that is Nike – on the way home from a party in Eugene, Oregon. He was just 24 years old.

His presence can still be felt strongly in the town. A plaque now sits at the crash site on Skyline Boulevard that has become known as “Pre’s Rock” and is a place of pilgrimage for athletics fans who leave shoes, shirts, medals, memorabilia and messages as an act of remembrance. In Eugene you can also run on Pre’s Trail or attend the annual Prefontaine Classic meeting.

“In the state of Oregon, he never died,” says his friend, former training partner and room-mate Pat Tyson, now Director of Cross Country and Track and Field at Gonzaga University in Washington state. “In that region, it's almost like a religion.

“And then you go out around America. I was recently at Stanford University [at an event with the kids I coach] and there was a gentleman there from the Washington DC area whose daughter is a volleyball player at Stanford. We were sitting in the hotel lobby, and he asked me where I went to school. When I told him it was the University of Oregon he said: ‘That’s a great track school. That’s where Steve Prefontaine went to school’.

“He asked me if I knew him and I said: ‘Well, we were room-mates’. I met that man again the next day and he’d researched me. ‘You weren’t lying!’ he said. A lot of people don't know our sport well in America any more, but they know the name Prefontaine.”

Grant Fisher, America’s 5000m and 10,000m Olympic bronze medallist from Paris last summer, is among their number.

“I grew up in Michigan and got into track when I was young, and one of the first names that you are exposed to is Steve Prefontaine. You don't really get exposed to the current pros as much as Pre, [who is] this transcendent figure. Some high school kids worship him.

“What other distance runner has had multiple movies made about him? And what other distance runner has posters that are on people's bedroom walls? Was he the greatest American athlete ever in track? No, but his impact transcends what he did on the track.”

Fisher’s point about Prefontaine’s athletics prowess is an important one. That he was a very, very good runner indeed is not in dispute. Having come to prominence with his high school record-breaking exploits, the Oregon native was just 19 when he was featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1970 with the accompanying headline of “America’s Distance Prodigy”. At the time of his death, he held every American record from 2000m to 10,000m and was never beaten over any distance over the mile on the University of Oregon track at Hayward Field.

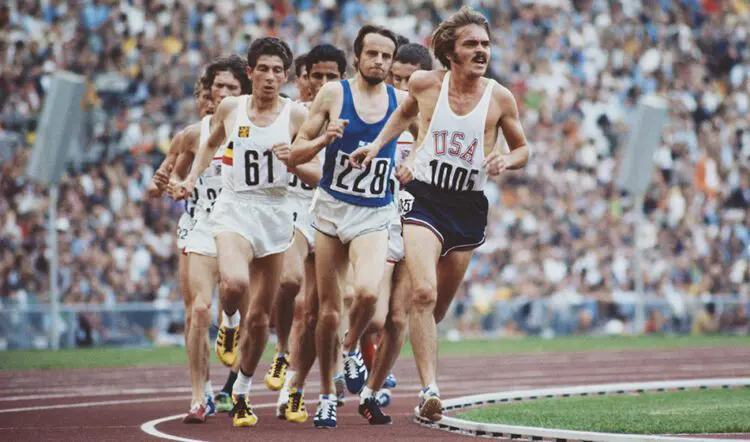

Yet, aside from his NCAA titles (there were seven in total), there were no major international medals in his collection. This was the era before the World Championships existed and his one Olympic experience, in Munich 1972, saw him finish fourth in the 5000m final despite his best efforts. There are other US distance runners who have reached far greater heights.

But none have struck a chord or lodged in the national consciousness in the same way since and his brief life really is the stuff of legend. Why? Let’s try and find out.

Pat Tyson will never forget his first meeting with Steve Prefontaine.

“It’s easy to remember because of his personality,” he says. “I had read his name first in [the magazine] Track and Field News and in 1968 I was getting ready to graduate. Coach Bill Dellinger recruited me to come to the University of Oregon and he wanted me to come down to a meet at Hayward Field [in August that year]. I’d never been there before and it was a very elite meet with a lot of the Olympians that were going to compete in the Games in Mexico City.

“He hooked me up with this [high schooler] Steve Prefontaine and we were room-mates in a dorm [over that weekend]. He was going into his senior year at high school and I was going into my freshman year at university.

“He was definitely not shy. He stood out in the way he walked, the way he talked – even then [aged 17] he liked to be the guy in the room. For example, we were in downtown Eugene at a sporting goods store and a guy working there was talking about ‘this guy named Steve Prefontaine, some hot shot from Coos Bay’ and Steve said: ‘Well, that’s me!’. He wasn’t going to shy away from it [and keep it to himself].

“That weekend, we were all over the place. We went to the track meet, and it was spectacular. It was a full house at Hayward with amazing races and Pre’s eyes were as big as silver dollars. I was quieter, I was more his shadow, but we were both stomping on the wooden stands and feeling the energy of the races.”

The spell had been cast, and when it came time for Prefontaine to start university life at the same campus, he wasted little time in making an impact.

“He was a star on the team immediately,” adds Tyson. “He was already great. I was trying to find my way. He was the man and there were some seniors who liked to put Pre in his place, but Pre didn't want to be in that place.”

He was also quick to be noticed by Bill Bowerman, head coach at the university. It was a handwritten note from Bowerman that had in fact brought Prefontaine, not short of offers, there in the first place. "It said if I came to Oregon, he'd make me into the best distance runner ever," Prefontaine recalled. "That was all I needed to hear."

Tyson adds: “To get Bill Bowerman’s attention was very challenging but Pre immediately got Bill Bowerman’s attention. I think Bowerman knew that he had himself an unusual character.

“The seniors that were already in place liked to make sure the younger guys knew their place before they moved up the ladder but Pre decided to move up the ladder quickly. He won the NCAA outdoor championships as a rookie, and he was third in the NCAA Cross Country Championships right out the door, so he had instant respect, but he was only 18,19 and still maturing. He was not bashful!”

Some would view Prefontaine as arrogant but Linda Prefontaine, Steve’s younger sister by two years who grew up with him in the coastal Oregon town of Coos Bay, takes issue with the idea that her sibling’s confidence spilled over.

“People in the track world might comment that he was cocky and brash, which to me is hysterical when you compare it to cocky and brash today,” she says. “He's not pounding his chest and doing a dance at the end of a race like they do [after a touchdown] in football or chest bump like they do in basketball and talking smack.

“He never did any of those things. He might have made a comment like: ‘I think I can do really well’ or ‘I think I might win’ but in comparison to the cockiness and brashness today…

“He never was that way around me. He was just my brother. He didn't have to put on anything around me. Because most people don't show you who they are, right? They put up a little bit of a front but, around me, he didn't have to do that. He had a lot of charisma. He had the ‘it’ factor. He was genuine. He genuinely cared about people.”

As a reporter with Track and Field News, Tom Jordan saw Prefontaine on the athletics circuit a few times but still didn’t know him too well when he had the encounter that springs most readily to mind.

“My most personal interaction with him was at the Los Angeles Times indoor meeting. It would have been 1975,” says Jordan, who would go on to write Pre: The Story of America's Greatest Running Legend, Steve Prefontaine.

“I remember sitting in the lobby of the hotel, and I was talking with a writer from another magazine and she was saying: ‘I just don't understand why people talk about Pre’s charisma. I think somebody like John Newcombe [a top tennis player at the time who wore a handlebar moustache] has a lot more of it’.

“I went into the bar, and it was pretty empty, and who should walk in, but Pre. He looked around and had his choice of any place to sit, but he came over to the bar and sat next to me. We knew each other by sight, but I'm pretty confident he didn't know my name, yet he struck up a conversation and, for the next half an hour, we talked about everything but running.

“He had this ability to make you feel like you were the only person in the room. [On that occasion] I pretty much was, but the point being that he focused his entire attention on who he was talking to. And this is a guy who had just been voted the most popular track and field athlete in America, had been on the cover of Sports Illustrated and all of that. To be the focus of his attention was really quite something.”

But Prefontaine was also adept at being the subject of others’ attention. Tyson has vivid memories of the times they would spend at a bar called The Paddock – where Prefontaine was a bartender for a while – and the track star would play pool, darts, the then new-fangled video games such as Frogger and Pong, and generally hold court.

“There was an elderly gal that worked at the kitchen there – we called her Aunt Bie – and she made these beautiful burgers,” says Tyson. “She just loved Pre and he loved her. Everyone loved her but, oh my god, when Pre got his burger it was bigger. His beer might have been taller, too.”

“The guy never missed a workout. I’m pretty orderly but he was beyond orderly”

Whether he liked it or not, Prefontaine also had a reputation as someone who liked to party.

To this day, rumours and counter rumours still swirl around the night he died. Earlier that evening he had competed in – and won – a 5000m race at the NCAA Prep meet at Hayward Field which had featured a group of traveling Finnish athletes.

He had left the post-meeting party to drive his friend and fellow athlete Frank Shorter to the house at which he was staying. After dropping Shorter off, Prefontaine continued down Skyline Boulevard, before his car left the road. Police reports stated he was over the legal alcohol limit.

To some his story is a cautionary tale of drink-driving, however Linda has always disputed the police findings and Shorter insists he would never have got in the car if he had thought Prefontaine was drunk.

It is also in stark contrast to how Prefontaine viewed other areas of his life and running in particular.

“In second year, he ended up joining a fraternity for about a third of a year,” recalls Tyson. Doing so, however, tends to result in a hard-drinking, pard-partying lifestyle that doesn’t quite match up with athletic pursuits.

“Pre realised you couldn't be a great athlete if you lived in the fraternity house. He got out and stayed with a friend for about a year-and-a-half before he bought a trailer.”

Prefontaine asked Tyson to live with him in that caravan. “I didn't see us rooming together during my career there, but that would evolve,” he recalls. “I got better [as an athlete], he respected that, and he invited me to be his room-mate.”

Living with the university’s track star provided a unique insight into how operated.

“The guy never missed a workout in four years in Oregon and you can't do that unless you have really good time management,” says Tyson. “It was probably from his German mum but he was very organised.

“The trailer was clean, perfect. He'd get up in the morning and make his bed immediately. It was like the military. The kitchen was perfect, his car was spotless and waxed, and I think that one of the reasons he liked me as a room-mate is that I'm pretty orderly, too. But he was beyond orderly.

“In the locker room, his locker was perfect and whenever we would go on a trip and there might be the expectation to wear a sports coat, Pre always looked like he’d stepped out of Hollywood.”

There was nothing out of place when it came to training, either.

“He was a master at knowing when to turn it on and when to turn it off,” adds Tyson. “When he was on his way to practice, got in the locker room, got his gear on and was working his way out to the track, it would be total focus. Again there would be attention to detail, that this would be the workout where he would master the intervals, repetitions, the tempo, whatever Bill Dellinger [had set for him to do].

“Bill Bowerman was the head track coach but Bill Dellinger was the distance coach, and he was the one that was there day by day and set all of the workouts. Pre had so much respect for Dellinger because he was a three-time Olympian who won the bronze medal in Tokyo [in 1964].

“Pre never questioned the workouts. He totally, totally trusted them. He executed them all perfectly, even when he didn’t feel very good. He was the first one to the locker room and he was the first one to leave practice. There was no wasted time.”

There was only one way to race, too. Hard and from the front.

“When I talked to Bill Dellinger back in the day, it seems like Pre ran pretty hard in a lot of small races where he didn't have to run hard in order to win,” says Jordan. “Dellinger would say: ‘All you need to do is view it as a workout or view it as a warm-up’ but Pre would go out and he’d say: ‘The fans expect me to put on a show’. So he'd go out, break away from what were pretty much mediocre distance runners, and yet still he'd push it. The fans here in Eugene have always been pretty knowledgeable, so to see someone who is their hero go out and push the pace hard when he didn’t have to made a real impact on them.”

His background did, too. Prefontaine, whose father Ray was a welder and served in the US Army in World War II, meeting his eventual wife and Steve’s mother Elfriede in Germany when he was in the US occupation forces, was no stranger to hard work.

“We were somewhat middle class, with hard-working parents, we didn't have everything given to us,” says Linda. “We lived a simple life and look what he did. He ran because he had a passion and a love for running and competing. That had nothing to do with getting paid anything and I don't think that's necessarily what drives athletes today.”

Prefontaine didn’t just use his force of personality to make himself popular with the Hayward Field crowd, in the university bars or with members of the opposite sex. If there was a cause he deemed to be worthy of fighting for, then fight for it he did.

“He was definitely evolving from that little cocky teenager,” says Tyson. “Oregon was always a school of activism. Our professors always preached activism. Reading about civil disobedience and then going out to practice civil disobedience was a theme during our period of academia there. And Pre did his part.”

There were two areas in particular where doing that “part” made a big difference.

The first was the matter of athletes being paid for their hard work.

“When he was running, European athletes were professional but United States athletes were not, they were amateurs,” says Linda.

The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) decreed that athletes who wished to remain “amateur” and be considered for Olympic selection could not be paid appearance fees at meetings, regardless of the crowds these events would draw or the money they would generate.

The AAU would also remove the amateur status of any athletes who were being endorsed by brands or companies and they decided that Prefontaine, still at college and running in clothing and shoes supplied by Nike, fell into that category. At one point, he was forced to live off food stamps.

He decided to take a stand and very publicly waged war on the AAU. Even the very last race of his life, at that meeting he had arranged with the Finnish team, was in defiance of the AAU stance on international competition. Three years after Prefontaine’s death, in 1978, Congress passed the Amateur Sports Act, which removed the AAU stranglehold and put into action many of the measures he had been advocating for.

“People today start grooming their kids when they're just out of the womb, and it's about getting good contracts and about getting all the attention, and that didn't exist back then,” says Linda.

“What’s happening today is a direct result of what he was willing to do during his time to make it better for all athletes, not just negotiate for himself. That's the other thing… to people who want to smack talk him, he was out there fighting for all the other athletes and not just himself getting the big contract.”

The impact of that fighting is still being felt today and Grant Fisher adds: “I think one thing that's a bit underrated about Pre, that athletes now don't really appreciate, is his fight against the AAU and the rise of professionalism in the Olympics specifically.

“A lot of that paved the way for guys like me. Back in the day, unless you came from money, it was really hard to train for Olympic sports, so his fight against the AAU and really trying to bring some professionalism to the Olympics, really did pave the way for a lot of professional athletes. I think those things would have changed eventually, but Pre was one of the figureheads of that movement and I think that's a little unappreciated [when it comes to] what his impact is today.”

Another of Prefontaine’s very public stands came in an area that had very little to do with sporting pursuits. After the harvest in late summer, the farmers of Oregon would burn the stubble of their fields – and the resulting smoke would descend and hang over Eugene.

“One year, several people died on the freeway when a farmer was burning the fields and the wind shifted,” recalls Linda. “All of a sudden, all that smoke was on the freeway and people just ploughed into each other. It’s also not healthy to breathe that crap.”

One of Prefontaine’s racing performances would underline that point. In early September of 1974, around 1000 fans had descended on Hayward Field to watch him take on a mile time trial as part of his preparations for a race in Europe where he was due to take on Brendan Foster.

He wouldn’t just be contending with the clock, though. On that day, the smoke from the fields hung thick over the stadium. Rather than exercise caution, Prefontaine ran in typically hard fashion to clock 3:58.3, but there would be a price to pay. He finished the race coughing up blood and with damaged lungs.

“What's often lost in talking about Prefontaine is how young he was,” says Jordan. “A mature runner might go out and say: ‘You know, I really wish I could run for you today, but the weather, the field burning is just too bad and I'd be happy to sign autographs’. They would have been happy as clams, because he would have been taking them into his world and saying: ‘It wouldn't be smart for me to run’ but his attitude was: ‘I can't let these people down’ and so he went out and ran 3:58.

“And then, of course, he coughed blood afterwards and that's the sort of thing that cost him later on in Europe. You can't simply damage your body that way and then expect to pick up where you left off.”

But Prefontaine had made a very public show of the field burning problem and would go on to testify to the State Legislature over the matter.

“He was part of that movement of trying to get that process stopped,” says Linda.

That wasn’t where his social conscience, or role in the community ended, either.

“He also would be going out to schools and just inspiring kids, middle school kids, elementary kids about athletics and running and anti-drug messages, that sort of thing,” adds Tyson.

“He was socially active because, after the 1972 Games, he would go to the Oregon State Penitentiary and befriend prisoners, then get them into jogging for their therapy.”

Prefontaine’s career development also happened to coincide with the emergence of a company called Blue Ribbon Sports, co-founded by Bowerman and Phil Knight, another Oregon alumni and track athlete.

Blue Ribbon would eventually become Nike but at the time it was a world away from the money-making machine that helped launch the likes of Michael Jordan, Andre Agassi or Tiger Woods into the sporting stratosphere.

“Nike was sort of finding their way, and I know Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman loved the guy [Prefontaine],” says Tyson. “That company needed a star to wear the product, to validate it, and Pre was cool.”

His style, character and demeanour mirrored Nike’s ambition to shake things up, too, and in Prefontaine they had found a perfect fit. So perfect, in fact, that it would help launch the 1970s running boom which proved transformational and brought the kind of mass participation running events that are so commonplace today.

Prefontaine began receiving an annual stipend of $5000 from the company in 1973. As nike.com documents: “He printed up business cards with the title National Director of Public Affairs, and began travelling around the Pacific Northwest sharing training tips and encouragement to athletes while introducing them to new Nike running shoes.”

It was a recipe for extraordinary success.

“He died in 1975 when the running boom was starting and it just went nuts after his death,” says Tyson.

Fisher is a Nike-sponsored athlete and confirms that the influence of Prefontaine, the subject of a number of marketing campaigns after his death, is still very much in evidence.

“His name is everywhere on the campus [in Beavertown, Oregon],” he says. “He has buildings named after him. There are little Nike display sets throughout the campus and so many of them are the original Blue Ribbon Sports story with Pre racing at Hayward Field and being coached by Bill Bowerman and all these things. And that's the roots of Nike.

“I think Nike kind of got away from their roots a little bit and, in the last year or so, there's been a big push to get back to their roots – grassroots running and this emotional storytelling.

“That's how it all began, with Pre, so it's cool to be a part of a brand that really revolutionised the running space and was one of the first brands to really rally around an athlete in track as far as sports marketing goes. I can look back and say thank you to the people that were making those decisions because, currently, my bosses are in sports marketing, and at Nike that was set in place with Pre.

“Now, speaking internally with Nike, there's going to be a significant push to get back to what Nike was founded on, and get back to running as the main thing. Some of those old Nike campaigns are iconic. I'm a Nike athlete so of course I'm a little biased here, but you know, some of those old posters, some of those old campaigns, that kind of set running sports marketing in motion.

“This brash, rebellious spirit is what Nike was founded on. I think they're trying to get back to that a bit, which is cool. In the past 10 years, when you see a Nike campaign for running, there's hardly ever Nike pros in the campaign.

“They're trying to get back to putting [the athletes] in the campaign, trying to use the athletes as the spokespeople again, and not the advertising consulting firm models as the backbone of the campaign.”

There is no specific moment Linda Prefontaine can pinpoint for when her brother moved into the world of sporting stardom and life truly changed for him. There is one moment, though, that still makes her smile.

“When he qualified for the Olympics, at the trials in Eugene,” she says. “Because that represented all the years of his training, and there was just that relief for me, happiness for him, that he was able to make it to the Olympics because that was the gold standard.”

He had booked his place for the 5000m in Munich in style by breaking the national record, clocking a time of 13:22.8. But he had barely had the opportunity to amass significant international experience ahead of jetting to Germany and Tyson remembers something different about his friend as he set off.

“At the airport on the way out to Munich he was nervous,” he says. “He grabbed me and you could feel his tight grasp. ‘I really don't want to go but I’m going,’ kind of thing.”

Tyson also remembers the attention that had surrounded Prefontaine in the build-up to those Games, recalling visits from Sports Illustrated, documentary makers and TV crews to their trailer. “There was a lot of pressure.”

He was to face the toughest test of his career to date. Lying in wait for the American hot shot were the likes of Finland’s Lasse Viren, who had already broken the world record on his way to 10,000m gold at those Games, defending 5000m champion Mohammed Gammoudi of Tunisia and Britain’s reigning Commonwealth champion Ian Stewart.

As if contending with all of that was not enough, though, the terrorist attack that saw 11 members of the Israeli team killed, completely changed how those Olympics would be remembered.

Accounts from the time report that Prefontaine was sleeping on the balcony of his overcrowded apartment in the athletes’ village when the first shots were heard close by.

It was a very different experience for Stewart, who had been oblivious to events.

“I had got up in the morning [after the attack] and had gone out for a run. I just went out the gates [to the athletes’ village]. Nobody stopped me and nobody stopped me on the way back in. I had a shower and then I went down for breakfast. That’s when I found out.”

The village was subsequently, and temporarily, cleared. Dellinger, working with the US team, took Prefontaine away to the house he was staying in outside of town. By the time Stewart – expecting to have to negotiate a heat, semi-final and final – was able to get back in, things had changed.

“By luck, I happened to bump into the British team manager,” he says. “He said: ‘There’s been a change to the 5000m. You won’t be racing tomorrow, and instead there’s a day of silence. But it’s now two rounds. There are five heats, two through in each heat, and the four fastest losers’.

“Whatever heat you were going to be in, you had your hands full. It was billed as the big race of the Games. Some of the coaches were just about having heart attacks with qualifying conditions like that.”

Prefontaine was second-fastest overall in making it to the final but, as Jordan points out:

“It was two days after the killings of the Israeli athletes, and the final was delayed by a day, and that upset Pre. I think it threw him off his stride a little bit. Then, of course, he was up against people who had talent similar to his or even better.

“Someone like Gamoudi had all those years of racing. I was in Munich, I was watching the race live and he cut Pre off, not once, but twice. For somebody like Steve, having a powerful stride was all-important, and to have that interrupted, you kind of have to shift gears and get started again. That's really tough to do if you're that build.”

Prefontaine had been in his customary position at the head of the field with 1600m to go and was soon at the front of a five-man breakaway. Viren went ahead with just over two laps to go, only for the American to move in front again before the Finn surged again just before the bell. Gammoudi reeled him in, though, as Prefontaine battled in third before surging in front once more. With around 150m to go, Virén made his decisive move and seemingly left Gammoudi and Prefontaine to battle it out for the other medals. The Tunisian clung on for second while Stewart, finishing like a train, stormed through to beat the fast fading Prefontaine to third.

“I think when I came across him in Munich he was at his best,” says Stewart. “I think he ran better than I did in Munich. In fairness to him, he had a right good go at it and I think he probably ran as well as he possibly could have done.”

There was a lot for Prefontaine to digest. Not only had he fallen short of his target but those events away from the track had also left their mark.

“When your goal is to win, not coming fourth, I think that was a huge disappointment,” says Linda. “He took time to analyse it, to figure it out. He fell off the horse but he got back on it and began to move forward. How can you pretend that everything's okay? When people are dying, you can't. Did it affect him? Of course.”

Tyson saw those effects up close but gave his friend space.

“I think one of the reasons he liked me is I never asked him [about it],” he says. “I never probed him. He came back to Eugene earlier than expected. He was going to hang out in Europe a little longer [after the Olympics]. I remember saving all the newspaper results and all the pictures of that Olympics but I went out of town for a couple days [at the time of Prefontaine’s return] and when I got back, he had taken all those pictures and articles, cut them out and put them in his own scrapbooks. But there wasn't much more. When he got back, he went to the dog pound and got himself a dog called Lobo. I think he just wanted to move on.

“He was unstoppable [in the US] and I think he was cocky enough to think he was unstoppable in Munich. He hadn’t had a lot of international experience but that confidence is what made him good, anyway. I know he spoke to others about it but we never brought it up and I think he respected me for that.

“He got fourth, he came back and he paused. But in the fall [of 1974] he won his last title so he was still driven. As he got closer to [the 1976 Olympics in Montreal], about a year before he died, he ran the fastest time in the world in late May. He set himself up pretty well to go back to Europe. He certainly wanted to run there again.”

Jordan concurs that Prefontaine had a very clear purpose.

“Pre’s real motivation was to come back in 1976 and win a medal,” he says. “And he might have been more attuned to the 10,000m. Even though he didn't have the slender build of a classic distance runner, he was so strong and he had such an incredible engine – his cardiovascular system and his heart – that you could make the case that he would be a gold medallist, or at least a medallist in Montreal. I tend to think that, had he won a medal, he probably would have retired and he would have been very successful at whatever he put his mind to.”

View this post on Instagram

The fact that we’ll never know what Prefontaine would go on to do next is another element that has added to his legend. “There are so many ‘what ifs’,” says Fisher. Parallels are often drawn between Prefontaine and James Dean, the tragic movie star who shone so brightly in his brief career and was also 24 when he, too, died in a car accident.

“He was this rebel figure and had a cult following, and then his early death … I don't want to say it amplified his platform, but Nike leaned into marketing really heavily with Pre in his final years, and especially after,” continues Fisher.

It’s tempting, and completely natural, to wonder how well Prefontaine might have done in the current track and field climate and what impact he might have made. Athletics is often cited as being in dire need of personalities, of individuals who will help create interest and widen the reach of the sport. Fisher insists that Prefontaine is managing to still do that from beyond the grave.

“Pre is very inspiring, especially for people who are just getting into the sport or trying to draw lessons from the sport to real life,” he says. “Did he always have the best racing tactics? No. So, as a professional, you might be like: ‘That guy could have been way better’. “But, as a high schooler, you're like: ‘Man, he goes to the front, he gives everything he has, and dares people to try to beat him and that's really fun and cool’. For a sport that generally isn't thought of as being fun and cool by high schoolers, it's a cool legacy to have.”

He adds: “Pre was a controversial figure, and that's what made him appealing. People talked about him whether they liked him or they didn't like him, and that's exposure of the sport. I wouldn't say there's anyone exactly like that right now, but if you're trying to change something in the sport, maybe controversy is a good thing.”

The movies made of his life – Prefontaine, Without Limits and the documentary Fire on the Track – are still often requested by high school or university athletics teams looking for inspiration the night before a big race. It’s another reason why his name remains in the public consciousness.

Since 2018, Linda has also conducted the Tour de Pre in Coos Bay – a private tour in which she tells her brother’s story, right from its very beginnings. “I wanted people to get a really great understanding of the area and how beautiful it is, and people get the history of what it was like when we were growing up,” she says. “The surroundings and the family, these are all things that affect who you are and who you become and so I teach people all about that, and I take them to the places where he trained, so they can literally run in his footsteps.

“When I’m talking to these people, especially the younger kids who come and are high school age, they’re runners and their parents have brought them. I'll ask them about Olympic gold medallists that are still alive today, specifically in running, and these young kids don't even know who they are. But they know who my brother is.”

The tour will be taking a hiatus this year and, not surprisingly, Linda finds the anniversary of his death particularly difficult.

“That's the worst day of my life,” she says. “May 30 changed the course of my family's life, and certainly affected the track and field community. It went beyond that, too, but it stopped my family in its tracks. I hate that day.”

She will mark it quietly this year, but will be part of something far more communal at what will be a very special staging of the annual Prefontaine Memorial Run – “a challenging 10km road race across one of his old training courses, with its finish line at the high school track where he first competed” – on September 20.

“I’m on the Prefontaine Memorial Committee and we're not going to celebrate the fact that he died 50 years ago,” adds Linda. “We're going to celebrate his legacy and the term I'm using is that people are going to run with the ‘Spirit of Pre’. We're not celebrating that he died, because that is not a celebration.”

She adds: “If you want to use a buzzword today, he was authentic. I think that's one of the reasons why he is still popular today. He was real and authentic, and that's something that's not very prevalent in today's world.”

It’s aspects such as the authenticity of the Prefontaine character that Tyson focuses on when he fields questions about his late friend. He tends not to speak too much about him unless prompted. “I don’t want the [college] kids to think that I’m just living in the past,” he says. However, it is another way of keeping that “Spirit of Pre” alive.

“Some kids might ask questions, or I might share with them what he taught me,” adds Tyson. I was not a super confident guy as a human being. As a runner, too. I was a bit shy, a little more timid. Pre would talk to me and, for example, if I worried too much he said: ‘What are you doing? You're not landing a multi-million dollar aircraft carrier in a storm or low on fuel. You're not in war. It's just running’.

“I learned from him and passed that on, hopefully successfully, to some athletes, that it's just sports. It's going to teach you a lot of lifetime lessons. Try to get confidence from the workouts, line up and go out and do your best, because Prefontaine always did his best.

He never had any regrets – win, lose or draw. He put himself in there and, more often than not, he won. But he took risks.

“‘You guys want to know about Steve Prefontaine? He was committed’. You see that in other sports, too – the great ones are committed. Pre was very, very good, but he wasn't blessed with an amazing amount of speed. He was blessed with grit, huge amounts of desire and I can only take that from him and share that with my athletes.”

Tyson likes to lean on the quieter memories, too, which were far removed from any glitz or glamour, his mind drifting to the calmness he saw when Prefontaine was working in the makeshift darkroom he had built in their trailer. “He liked black and white prints and loved to go out and take pictures of nature, so there was that side of him,” he says.

“I don't have many dreams about Steve. Over the last 50 years, I've only had a couple, but I actually had one really recently. And what I liked about it was it was just a common day. We were in Coos Bay, walking around, we went to a diner, he was smiling, it was nothing out of the ordinary. It was more about him being the simple guy, on the street, talking to the locals. I didn’t really want to wake up. It was kind of fun to have a dream like that, just because those were really, really great memories with him.

“He gets to stay with me because kids are still asking questions all the time. People still ask questions, so he’s still alive and making a difference in our sport, and the lives of others.”

“An event like no other” – 50 years of the Prefontaine Classic

One of the greatest memorials to Prefontaine is the annual staging of the Prefontaine Classic, which has become one of the great athletics meetings and a key fixture on the Diamond League calendar that attracts the finest athletes on the globe.

The event began life in 1973 as the Hayward Restoration Meet, staged by Bill Bowerman and the Oregon Track Club to do exactly what the name suggests and raise funds to redevelop areas of Hayward Field.

Prefontaine raced in that inaugural meeting, and at its follow-up one year later, but in 1975 it had been due to be renamed the Bowerman Classic. The star athlete passed away just over a week before it was due to take place though and, on June 7, the first Prefontaine Classic went ahead. “Pre 50” will be staged on July 5 this year.

AW columnist Katharine Merry has worked at the event every year since 2009, first presenting from the infield and now working as stadium announcer.

“Every single year it is an absolute privilege and pleasure [to be involved]. And you can still feel the strong Prefontaine connection,” she says. “You can't go anywhere without seeing the hat being tipped to him in Eugene. It’s a meeting like no other.”

Tom Jordan was the meeting director for now fewer than 37 editions – between 1984 and 2021. When he first started: “Nike put in, I think, $25,000 which was good money money for a domestic meet but not an international meet like Lausanne or Zurich.

“I knew what the standard was in Europe, but it wasn't that way in the US. It wasn't really until the early 90s, when Nike decided to put in more resources, that it took off. It's been pretty much an upward trend since then.

“I now see people in the field that are children of athletes who competed in the Pre Classics of 20 or 30 years ago, and that's kind of sobering and also kind of neat.

“Over the years, I've been asked many times: ‘What was the big deal about Pre?’. You have to understand that it was a real connection between him and the fans. They loved him and so you can't look at it in terms of honours, it's more [about] what kind of relationship did he have?

“I would have thought that by, say, the late 80s, the interest in Pre would wane [and it would become the case] where it's not so much the person that people remember so much as the fact that the meet is named after that person. But it didn't happen that way. The kind of serendipitous deal with Pre was that he got a start with Nike and, after his death, Nike worked to develop that brand and that kept something alive.

“I will say, I think my book was also a factor, but also you had a case where nobody was taking his place. It's not like there was a really great distance runner who had that kind of flare, or even a different kind of flare, so people looked around and said: ‘Well, where's the next Pre coming from? There was a realisation that it's not something that you can just conjure up. Here was this kid who was from Oregon, went to the University of Oregon, and put on a show.”

Pre's famous quotes

“A lot of people run a race to see who’s the fastest. I run to see who has the most guts”

“The best pace is a suicide pace, and today looks like a good day to die”

“To give anything less than your best is to sacrifice the gift”

“Somebody may beat me, but they are going to have to bleed to do it”

“I'm an artist. I perform not with a paint brush or a camera. I perform with bodily movement. Instead of exhibiting my art in a museum or a book or on canvas, I exhibit my art in front of the multitudes.”

“When people go to a track meet, they're looking for something, a world record, something that hasn't been done before. You get all this magnetic energy, people focusing on one thing at the same time. I really get excited about it.”

Steve Prefontaine’s most significant races

25.4.69 Corvallis 2M, First, 8:41.5 (US junior rec)

29.6.69 AAU 3M Championships, Fourth, 13:43.0

19.7.69 USA v USSR 5000m, Fourth, 14:40.0 (international debut)

31.7.69 USA v Europe 5000m, Third, 13:52.8

13.8.69 USA v GB 5000m, Fourth, 14:38.4 (1st Dick Taylor 13:29.0 (UK record)

20.6.70 NCAA 3M Championships, First, 13:22.0

26.6.70 AAU 3M Championships, Fifth, 13:26.0

19.6.71 NCAA 3M Championships, First, 13:20.2

25.6.71 AAU 3M Championships, First, 12:58.6

3.7.71 USA v USSR 5000m, First, 13:30.4 (USA record)

2.8.71 PanAm 5000m Championships, First, 13:52.6

29.4.72 Oregon 5000m, First, 13:29.6 (USA record)

3.6.72 NCAA 5000m Championships, First, 13:31.4

24.6.72 Gresham 3000m, First, 7:45.8 (USA record)

9.7.72 Olympic Trials 5000m, First, 13:22.8 (USA record)

3.8.72 Oslo 3000m, First, 7:44.2 (USA record)

24.8.72 Munich 2M, First, 8:19.4 (USA record)

10.9.72 Olympic 5000m, Fourth, 13:28.3 (First Lasse Viren 13:26.4)

13.9.72 Rome 5000m, Third, 13:26.4

24.3.73 Bakersfield 6M, First, 27:09.4 (USA record)

14.4.73 Eugene 1M/3M, First, 3:56.8/13:06.4

9.6.73 NCAA 3M Championships, First, 13:05.4

16.6.73 AAU 3M Championships, First, 12:53.4

20.6.73 Eugene 1M, Third, 3:54.6

27.6.73 Helsinki 5000m, First, 13:22.4 (USA record)

28.6.73 Helsinki 1500m, 11th 3:38.1

27.4.74 Eugene 10,000m, First, 27:43.6 (USA record) (26:51.4 USA 6M record during race)

8.6.74 Eugene 3M, First, 12:51.4 (USA record)

26.6.74 Helsinki 5000m, Second, 13:21.9 (USA record)

2.7.74 Milan 3000m, Second, 7:42.6 (USA record)

18.7.74 Stockholm 2M, Third, 8:18.29 (USA record)

26.4.75 Eugene 10,000m, First, 28:09.4

9.5.75 Coos Bay 2000m, First, 5:01.4 (USA record)

29.5.75 Eugene 5000m, First 13:23.8 (final race)

The movies

Prefontaine (1997)

Without Limits (1998)

Fire on the Track: The Steve Prefontaine Story (1995)

The book

Pre: The Story of America’s Greatest Running Legend by Tom Jordan