Around two thirds of British athletes in teams for recent major championships have been helped by the Ron Pickering Memorial Fund at some stage. The charity, among other things, helped Mo Farah buy his first pair of running spikes when at the time football boots were probably more tempting. Its impact on domestic track and field has been huge as it has given more than £2 million to talented young athletes for 30 years. Yet how much do you know about the inspiration and name behind the fund?

The eponymous Ron Pickering was a teacher, athletics coach and one of the best-remembered sports commentators on television. At the height of his powers, though, aged only 60 on February 13 in 1991, he died from a heart attack.

The sport mourned and the BBC ran special tribute programmes on television. But his spirit has survived in the shape of the memorial fund set up by his family, with many of the most successful athletes in Britain having benefited from its generosity over the years.

Pickering was born in Hackney on May 4 in 1930 and was a talented young sportsman himself. He had football trials with West Ham Utd but later conceded in self-deprecating fashion that he was “too big, too clumsy and to try another game”.

He went on to be head boy at Stratford Grammar School where he met his future wife, Jean Desforges. “She was the real athlete, not me,” he once said. “The boys at the school were scared of her. She could beat us at the long jump and high jump. She was very special.

“She trained (during the war) over three hurdles made in the school woodwork room and which were placed in the school corridor. I was one of the boys who stood at the end of the corridor to help stop her falling down the stairs. Out of that grew a romance. And I learned athletics by carrying her bag around the world.”

Indeed, Desforges won long jump gold at the 1954 European Championships, 4x100m gold at the 1950 European Championships and Olympic 4x100m bronze in 1952. They married in 1954 and had a daughter, Kim, and son, Shaun, the latter of whom competed at the 1996 Olympics and won a Commonwealth shot put bronze in 1998.

At school Pickering found himself often acting as an unofficial ‘minder’ or ‘school policeman’ who would break up the frequent fights that erupted among boys in those days. Later, after gaining a diploma in PE from Carnegie College in Leeds and a degree in education at Leicester University, he returned to the same school as a teacher.

His wedding international news headlines and was attended by thousands, largely because of his wife’s fame as an athlete. “I was the unknown school teacher marrying the great Jean Desforges,” he said.

After spells teaching at Stratford and Wanstead County High School, Pickering landed a dream job as National Coach in Wales. He held the post for five years in the early 1960s, where he spent the majority of his time travelling to various schools and colleges acting as a coach to fellow coaches or PE teachers. But, driven by his own slightly maverick tendencies, he left and moved back to London with feelings of frustration at what he felt was a ‘parochial attitude’ at the time in the country.

“When he resigned,” BBC commentator David Coleman later recalled, “the sport lost a man who could not only motivate but had a rare gift of communicating technical knowledge – a talent he (later) displayed so well with the BBC.”

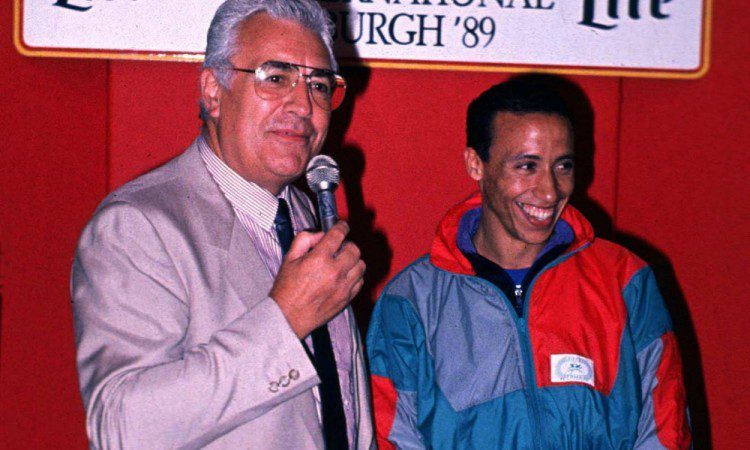

One Welsh athlete who did not have this parochial attitude, though, was Lynn Davies. The long jumper (pictured above with Pickering) reached global fame by capturing the Olympic title in Tokyo in 1964 and did so under the guidance of Pickering.

On first seeing Davies, Pickering was in awe of his talent and said to him: “I know what the great game of rugby means to Wales but I believe you can be the greatest athlete Wales has ever seen. If you want, you can be the first athlete in my squad.”

Davies later said of his coach: “He made me believe in myself. I knew when I walked into the Olympic Stadium in 1964 that I could win a medal.”

Moving back to London, Pickering got a job as Recreation Manager to the Lee Valley Regional Park. Again, he began to make a huge impact as he turned the area – and Haringey AC – into an epicentre of world-class athletics. Ever the visionary, he even suggested it would make a great venue for the Olympic Games.

Athletes such as Seb Coe were drawn to the Haringey club, with decathlete Daley Thompson training there too despite not being an actual Haringey member.

Thompson once said of Pickering: “Over 15-16 years I got to know him very well. I lived with him for six or seven months and shared his home with his family. I wasn’t alone either because he was so committed to sport. As a father figure he was always there with advice when I needed it and always there with advice when I didn’t need it too!”

Coe first met Pickering in 1977 and has described him as being instrumental when it came to joining Haringey when he moved from Sheffield to London in the 1980s. “Ron had a strict code of values and of course everyone had to pay club membership,” says Coe, adding that Pickering used to carry Coe’s club membership cheque in his pocket to show people that even Olympic champions had to pay to join.

“I never stand up and speak about Olympism without quoting Ron and one of the quotes I use is that Olympism wouldn’t have survived three weeks, let alone 33 centuries, if it had been based on anything other than open, free and fair competition,” says Coe.

One of the athletes Pickering helped in north London at this time was a young Tony Jarrett. The sprint hurdler went on to be a double Commonwealth champion in the 1990s and twice silver medallist at the world championships, but his success was partly down to Pickering keeping him on focused on athletics during a teenage period where things could easily have gone astray. Looking back, Jarrett is now seen by the Pickering family as “the model” for the memorial fund that operates today.

During these years in Wales and then north London, the Pickerings operated what they called “an open house” for athletes. It was a remarkable scenario where up-and-coming athletes, including some of the most talented in history, regularly spent the occasional night or weekend or even days or weeks on end sleeping and eating under the same roof. As Pickering himself once said: “The house is almost designed to put athletes up in every room whether it’s the kitchen, lounge, study or anywhere else.”

When Shaun Pickering went away to study at college, for example, Daley Thompson moved into his room for a spell. In addition to Davies, Thompson and Jarrett, other athletes who Pickering gave help to included Tessa Sanderson, the 1984 Olympic javelin champion. However, the list of athletes who stayed at their house is huge and a special visitors’ book which the Pickerings kept contains a who’s who of famous names.

These names included Mary Rand, the Olympic long jump champion in 1964, who later recalled: “Ron and Jean became my dearest friends and some of my happiest memories are from spending time at their home. John Le Masurier coached me but Ron would always help me out if I was at meetings – he was a big influence and died far too young and I miss him to this day.”

On one occasion, Pickering was commentating for BBC on the annual Zurich meeting. An American 800m runner called Ray Brown was pacemaking but there were no biographical notes for the media about him. Improvising, Pickering merely said that Brown was not on the commentator lists ‘but I can tell you a bit about him because he’s been sleeping on my floor for the past few weeks!’

The set-up worked so well largely because Jean had been a world-class athlete, so she understood the peculiar personality traits of top athletes and the support they often required. She took up the baton after her husband died, too, putting countless hours into building the memorial fund until she, too, passed away in 2013 aged 83.

“If my dad saw a talented person coming through, he’d find a way of helping them,” says Shaun, who with sister Kim now runs the fund with a group of former athletes that include Davies, Stuart Storey, Goldie Sayers and Jo Summers (nee Jennings).

In parallel with this, Pickering built a reputation as one of the top BBC sports commentators. He was commentator initially at the 1968 Olympics and continued for more than 20 years. As well as athletics, he worked in sports such as gymnastics and skiing and was host of the popular BBC programme We Are The Champions and co-presenter of Superstars.

Ironically, Pickering sometimes said he yearned for a better and more authoritative voice. He was wrong, because his voice was distinctive and iconic and his commentaries still put a shiver down the spine when they are recalled today on YouTube or re-played on BBC.

After having helped create the Haringey environment, he became president of Haringey AC for 17 years and in 1986 was awarded an OBE for services to sport. “He took a disused rubbish tip in White Hart Lane and built it up into a club,” says son Shaun. “And it became a special place because of the atmosphere. We had 27 different nationalities who would turn up on a typical training night.

“On the night Broadwater Farm was erupting in race riots (in 1985), just one mile away we had 300 kids on the track training for athletics. One thing my dad was proud of saying was that he had a public pay phone with a white wall behind it and no graffiti. It said that this was what the club was like in that people respected the facilities.”

The facilities at Haringey included an indoor athletics hall as well. Shaun recalls of his father: “He used to say, ‘Newton’s fourth law – where there are no pole vault pits there will be no pole vaulters’. So to have an indoor hall next to the track was important and it created a great environment.

“This is what we’ve tried to keep going with the fund. Not only the ‘supportive’ nature but also the ‘opportunity’ and bringing people together. It’s important for us to try to keep these things going.”

Today most of the grants from the fund are what Shaun describes as a simple “tap on the back” for an athlete and recognition that someone, somewhere believes in them. But he adds: “The memorial fund is partly about keeping the things he (Ron) believed in alive. Fair play, anti drugs and giving talented kids a chance.”

So how to sum Pickering up? As Davies has said: “Ron was the conscience of the sport and the guardian of the sport.”

In 2001, on the 10th anniversary of his death, one of his friends and colleagues, Tony Ward, wrote these words in AW: “Ron was more than just a commentator. He was a visionary, teacher, coach, inspirer, crusader, believer – believer in the intrinsic values of sport, believer in the worth of sport to young people, believer in the principles of life and sport that his mentor, Geoffrey Dyson, had part instilled in him. Above all he was a master communicator.”

Indeed, London Marathon co-founder Chris Brasher described Pickering as ‘the great communicator’ and he was also one the last people to see him alive.

Pickering had undergone a 17-hour open heart surgery four months before his death. On the day before he died he had lunch with Brasher and John Disley, where he was talking as enthusiastically as ever about the sport and making light of his health issues.

Brasher, who since died in 2003, wrote at the time: “Next morning, I heard on the radio the Ron was dead. I felt as if I had been robbed. I knew that sport had been robbed of a champion — the greatest defender we have ever seen in this country of the purity of a simple sport which traces its lineage to the days when man lived as a hunter and survives through his ability to run, jump and throw.”

As for the fund created in his memory, who knows, perhaps Farah might not have gone on to win all his global track titles if he had not had a small helping hand in the shape of a grant all those years ago.

“The Ron Pickering Memorial Fund were extremely helpful to Mo at a time when he needed support most,” his former PE teacher, Alan Watkinson, told AW last month. “It is really important that funds like this exist to help athletes who would not ordinarily have the means to pursue the sport to the best of their abilities.”

From early recipients of grants such as 400m runner Katharine Merry, middle-distance man Vince Wilson and high jumper Steve Smith, the Ron Pickering Memorial Fund continues to help talented British athletes aged 15-23.

Almost 200 young athletes have this year received a cash boost from athletics charity despite pandemic-related fund-raising problems. These include Amy Hunt, Keely Hodgkinson, Lucy-Jane Matthews and Lewis Byng.

The charity’s main method of fund raising is the London Marathon but the cancellation of its mass race in 2020 put the memorial fund in jeopardy. However, the virtual event in the autumn led to a number of “Ronners” completing 26.2 miles and raising valuable funds in the process.

After this the long process of picking the athletes who receive the grants was carried out over a nine-hour session on zoom. As always, two main factors are considered – the ‘performance’ element of where athletes sit on rankings and what they have achieved in competitions – and the ‘need’ element, where family background and potential hardship cases are evaluated.

Sometimes difficult decisions are made, too, where an athlete’s grant is stopped in order to give younger up-and-coming athletes a share of a grants pot that this year totalled around £30,000.

In addition to the many smaller grants, some athletes are given more help via, for example, the Jean Pickering Scholarships, where athletes like heptathlete Niamh Emerson and hammer thrower Taylor Campbell have received support in the run-up to the Tokyo Olympics.

Other athletes supported by the fund this year include sprinter Charlie Dobson, middle-distance runners Isobel Boffey, George Mills and Oliver Dustin, hammer thrower Charlotte Payne, long jumper Reynold Banigo, high jumpers Kelechi Aguocha and Sam Brereton, heptathlete Holly Mills and para athletes Gavin Drysdale and Kayleigh Haggo.

» An edited version of this feature appears in the February issue of AW magazine. To find out more about the Ron Pickering Memorial Fund click here

» For more on the latest athletics news, athletics events coverage and athletics updates, check out the AW homepage and our social media channels on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram