This summer has seen some spectacular performances by young athletes but bridging the gap from junior to senior success is one of the trickiest tasks in the sport

Some of the most eye-catching performances in recent days have been achieved by young athletes. From 16-year-old Cooper Lutkenhaus’ 1:42.27 over 800m at the US Champs to 15-year-old Kelly Doualla’s sprinting excellence at the European Under-20 Championships in Tampere, teenage athletes are helping light up the 2025 summer track season.

We will even see some of these athletes at the World Championships in Tokyo in September. Lutkenhaus, for starters, has already booked his place in the United States team. After turning 19 in April, Innes FitzGerald is a little older but she has only been training seriously for three or four years, won a golden double in Tampere this month and is hoping her European under-20 5000m record of 14:39.56 set in London last month is enough to get into the GB team for Tokyo.

As any experienced coach or long-term fan of athletics will know, though, teenage triumph do not guarantee senior success in future. For every Usain Bolt there are countless teenage ‘phenoms’, ‘talents’ and ‘prodigies’ who fall by the wayside during the notoriously tricky transition into the senior ranks.

The first European Under-20 Championships I covered for AW was the 1999 event in Riga. The golden girl of the championship was German sprinter Sina Schielke after winning the 100m, 200m and 4x100m titles during a red-hot few days in the Latvian capital.

Although she went on to run slightly quicker in 2001-2002, it’s fair to say she didn’t reach the same heights as a senior sprinter and instead ended up on the cover of Playboy magazine in 2005.

At those same championships in Riga, Yuriy Borzakovskiy won the men’s 800m ahead of Nic Andrews of Britain. Yet demonstrating the fickle nature of athlete progression, the Russian went on to win Olympic gold in 2004 whereas Andrews struggled to run any faster than the 1:49.08 he achieved that summer.

Perhaps the most dramatic example of all comes from the 2002 World Under-20 Championships in Jamaica. Racing on home soil and just a month before his 16th birthday, Usain Bolt sped to victory in the 200m. The women’s 200m winner at those same championships, however, Vernicha James of Britain, only competed for a further two seasons before packing up due to injuries and disillusionment.

In the women’s 200m in Britain alone, in fact, the event is littered with great teenage runners who struggled to fulfil their potential. Amy Spencer was a top teenage sprinter at the turn of the millennium and was named BBC Young Sports Personality of the Year in 2001, but by 2005 she had quit athletics. In the same period, Sarah Wilhelmy was once billed as “the next big thing” but also quit soon after moving from the teenage to senior ranks.

Of course, some do make it. Dina Asher-Smith was a terrific teenage runner and went on to break UK records at 100m and 200m. Jodie Williams, who enjoyed an immensely successful period as a teenage sprinter, battled multiple injuries over many years to eventually finish a fine sixth in the Olympic 400m final in 2021 and in addition won Olympic relay bronze in Paris 2024.

What's more, it's good to see Amy Hunt, the UK under-20 record-holder in the women’s 200m, now successfully negotiating the junior-to-senior transition. Hunt has found her way to “the other side” and she won the UK 100m title in Birmingham this month.

Some of the most notable “teenage talents” who struggled to make their mark as seniors are etched in athletics history.

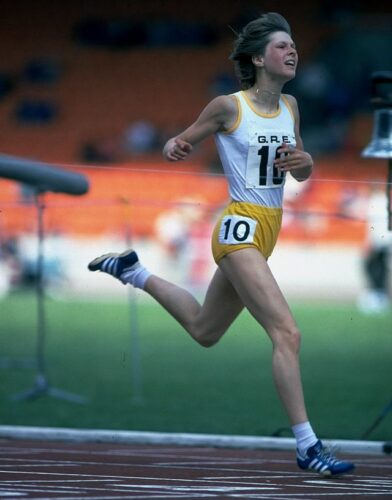

Linsey Macdonald was only 16 when she won the British 400m title in a national record of 51.16 and went to the 1980 Moscow Olympics where she reached the final. But her athletics career didn’t progress – although her age-group records certainly stood the test of time – and she became a doctor.

Ade Mafe reached the Olympic 200m final aged 17 in Los Angeles in 1984 and went on to win European indoor gold and world indoor medals. But by the mid-1990s he was pursuing a successful career as a fitness coach for football clubs such as Chelsea. Similarly, Harry Aikines-Aryeetey won a world junior 100m title in 2006 and, although not quite reaching the same heights as a senior, he won multiple sprint relay medals before achieving fame as "Nitro" in Gladiators and now, aged 36, becoming a Strictly Come Dancing competitor in coming weeks.

Kirk Dumpleton famously beat Steve Ovett and Seb Coe in the same race to win the 1972 English Schools cross-country crown and he went on to run well for a number of years, although obviously not at the same level as Ovett and Coe.

Female teenage middle-distance runners seem to attract the title of ‘teenage prodigy’ more than most. Georgie Clarke, for example, won the 1999 world under-18 title at 800m and one year later competed for Australia at the Sydney Olympics amid considerable hype at the age of just 16. Again, her performances dried up once she hit the senior ranks.

Similarly, Mary Cain raced in the 2013 World Championships aged just 17 and then won the world under-20 title at 3000m in 2014 but her results tailed off dramatically as she endured what she called a “toxic culture” under the coaching of Alberto Salazar.

Back in Britain, Emily Pidgeon (above right) was dubbed the “new Paula Radcliffe” and her many teenage triumphs included the European junior 5000m title, which came just a few weeks after her 16th birthday and London’s Olympic bid victory in July 2005. As she moved into the senior ranks she continued to post times that most athletes would kill for, but she hung up her spikes in 2014 at the age of just 24.

In 2016, the former AW editor Mel Watman did his own survey of young athlete statistics, looking at what happened to the 90 winners of English Schools track and field titles at the 2006 championships.

A decade later, when the athletes would have been aged between 24 and 29 years old and at the peak of their careers, Watman found that just 11 of the 42 winners of girls’ events and eight of the 48 boys’ winners went on to gain a senior international vest.

Meanwhile, in studies conducted at Liverpool John Moores University by the former GB heptathlete and sprint hurdler Dr Karla Drew as part of a PhD, it was revealed that 63 per cent of those who competed for Britain at the World Junior championships in 1998-2012 did not achieve a PB as a senior and 67 per cent of that group did not gain international honours as a senior athlete.

Reasons for athletes dropping out range from injuries and illness to exam pressures or alternative interests such as a career, boy/girlfriend or even a different sport. There are also more nuanced reasons, such as athletes who are narrowly beaten as teenagers retaining the hunger to train, whereas in comparison the kids who “win everything” can get complacent.

After covering the junior athletics scene for AW for a quarter of a century, here are some of my conclusions...

For every national senior champion or Olympian there are countless “teenage talents” who drift away into mediocrity or quit completely. Teenage drop-out rates are unfortunately savage.

If you are a parent or coach, don’t assume your talented child will make the top. The odds are not in your favour, but this shouldn’t stop you giving them the best possible support and encouragement.

Here’s the thing, you will struggle to find an Olympic gold medallist or world record-breaker who was not taking their athletics pretty seriously in their mid to late teenage years.

Remember, it’s better to win national or international titles as a junior than to never win anything at all. Many of the critics who point to young athletes “not fulfilling their potential” have more often than not never won anything themselves. Being the best at your event on a particular day against athletes in your age group is definitely something to be applauded.

Win or lose, teenage athletics competitions provide fond memories that last a lifetime. Competitors in Tampere and elsewhere this summer shouldn’t forget this. They might never make an Olympic podium but they will still have achieved more than most athletes can dream of.