It was my first year as a full-time athlete in 1996. I got an Olympic silver from the relay in Atlanta and was fifth in the individual 400m. In 1997, I got the British record. I was in the shape of my life but I totally messed up the World Championships final, coming sixth, and all I came away with was a relay medal, which was then promoted to gold years later.

For the 1998 season, it was all about how I had to win an individual medal. I just said to my coach, Mike Smith: “I have to win something this year.”

I was training with regular guys – 46-47-second runners. A guy called Tim Odell was my best training partner and his PB was 46.3. Lee Fairclough’s best was 47.8 but go out on the sand dunes in Southampton on a Sunday and he was an animal. I would use my training partners to my advantage.

I would train in lane three and I'd make sure Odell was in seven so I had someone to run down. Their ability wasn't as important as their personalities and their understanding of my needs, as well. It was a brotherhood, it was different and I never questioned my coach's training. He was a master at getting me to peak at the right time.

But the season hadn't gone so well because I'd had a few injuries and, on the grand prix circuit, Mark Richardson had beaten me five times out of five. Going to the AAAs, the trials for the European Championships, I spoke to my coach about how Mark was beating me. Mike said: “He hasn't got the beating of you when it comes to three rounds in three days. That's what your training is all about. Your strength is your strength. You can do it.”

That was the beauty of it at that time – if you were Britain's best over 400m, you knew damn well you were going to be top five in the world. To beat Jamie Baulch wasn't an easy thing. To beat Mark was difficult and it was the same with Roger Black. Then throw Du’aine Ladejo and Solomon Wariso into the mix. It was really good.

I was really proud to be around a golden generation and a time when to be the British champion really meant something.

In 1996 I came third in the trials in 44.7 in the year Roger broke the British record and I remember thinking: “It's my first year training, I'm getting close to these guys. I reckon I can be better than them.”

It happened the year afterwards. I was proud to be able to run with them because, of course, it meant we had a really good 4x400m team. The guys who I was trying to beat week in week out, all of a sudden became my team-mates at major championships.

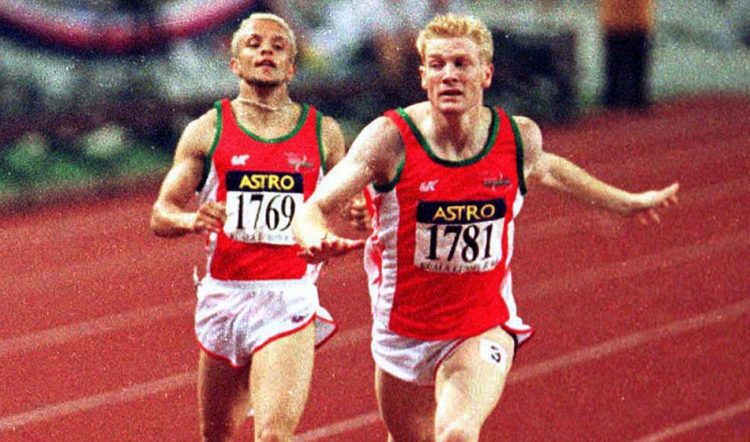

That was the weirdest thing. Take the European Championships in 1998. I shattered Mark’s dreams when I became champion but then, the next day, we shook hands and we’re mates in the relay.

But the rivalry was quite strange. People thought me and Mark didn't like each other. I actually really had a soft spot for him. Although he was my biggest rival domestically, I really liked him then – and now – but I'd growl at him on the warm-up track and I'd eyeball him and try and get inside his head.

That wasn't through disrespect, or lack of compassion towards him. Quite the opposite. I felt threatened by him. I knew he was my biggest rival so I thought: “If I can try and dent his confidence, I will.”

I hadn't told the press I'd had a few injuries in the winter [leading into the 1998 outdoor season] but me and Mark both started that season so well. We both beat Michael Johnson in Oslo and Mark nearly got my British record. I thought: “God, he is going to run so fast this year.”

My race plan at the AAAs was always the same: just go out hard for the first 100m, relax and maintain it down the back straight and then work the top bend so you come off with 110m to go and everyone's under pressure.

Normally I'd want to be in front. I wasn't naturally as fast as either Roger, Jamie or Mark over 200m but my speed endurance was insane. I could bang out 300m reps in Southampton in whatever weather and recover quickly, so I knew if I was there or thereabouts with 100m to go, my strength would pull me through. And that’s what happened.

I just came off the top bend in that final thinking: “You're the person they all want to beat.” In my mind, I just had to beat Mark because, if I did that, I was going to make the team. It wasn't my fastest race by any means, but it's the way I won it. I was about three or four metres off Roger and Mark with 100m to go. I didn't panic, my strength came through and I just kept going to the line.

READ MORE: AW's greatest race series

That was the first time I beat Mark. Roger came fourth and didn't make the team. When I won, there was a celebration. I knew that, by winning, I had secured my future. If I hadn't come in the top three, or arguably won that race, I wouldn't have gone to the Europeans and won that. I wouldn't have gone on to win the World Cup. I wouldn't have gone on to win the Commonwealth Games.

That was the turning point for my year. Also, I knew I could beat Mark. It went from 5-0 to 5-1, and then Europeans made it 5-2. Then the next race was 5-3. When I beat him at those trials, it was not relief. It was like: “Yes, now it's my time.”

» This article first appeared in the August issue of AW magazine, which you can buy here

» Special offer – buy our World Champs review issue for only £1 here