There is an all-too-common misconception that one can prepare sufficiently for a marathon by simply running three days per week, provided one of those days includes a gruelling 20-mile (or more) long run. That sounds simple, but the truth is that there’s a lot more to successful preparation than that.

All runs are not created equal, and the long run, while key, is merely one component of a larger system that prepares you for success in the marathon distance.

The Hansons programme has become known for the “16-mile long run” and a six-day-per-week running schedule that includes several types of workout. Our approach has sometimes been perceived as renegade when compared with status quo programmes on the market, and some runners have had their doubts when we promise they’ll set a PB with our programme. In fact, in the first edition of our book Hansons Marathon Method, we shared the story of Kevin Hanson’s wife performing marvellously using our method, albeit all the while intending to prove the method wrong.

Since then, I’ve received similar emails, with runners who had been fired up to write a scathing “I told you so” instead thanking us for their PB and confessing that they never should have doubted the process. I don’t write these stories to gloat, but rather to show by example that there is more to successful marathon training than a few runs a week plus a long run. And while people tend to have laser focus on our 16-mile long run, they really have to embrace the whole picture of what the method entails.

Let’s take a look at the long run the Hansons way.

The long run garners more attention than any other component of marathon training. It has become a status symbol among runners in training, a measure by which one compares oneself against one’s running counterparts. It is surprising, then, to discover that much of the existing advice on running long is misguided.

After relatively low-mileage weeks, some training plans suggest back-breaking long runs that are more akin to running misadventures than productive training. A 20-mile long run at the end of a three-day-a-week running programme can be both demoralising and physically injurious.

The long run has become a big question mark, something you aren’t sure you’ll survive, but you subject yourself to the suffering nonetheless. Despite plenty of anecdotal and academic evidence against such training tactics, advice to reach (or go beyond) the 20-mile long run has persisted.

It has become the magic number for marathoners, without consideration for individual differences in abilities and goals.

While countless marathoners have made it to the finish line using these programmes, the Hansons marathon method comes to the table with a different approach. Not only will it make training more enjoyable, it will also help you cover 26.2 more efficiently.

While our long-run approach may sound radical, it is deeply rooted in results from inside the lab and outside on the roads. As I read through the exercise science literature, coached the elite squad with Kevin and Keith, and tested theories in my own training, I realised that revisions to long-held beliefs about marathon training, and in particular long runs, were necessary. As a result, a 16-mile long run is the longest training day for the standard Hansons programme. But there’s a hitch. One of Kevin and Keith’s favourite sayings about the long run is: “It’s not like running the first 16 miles of the marathon, but the last 16 miles!”

What they mean is that a training plan should simulate the cumulative fatigue that is experienced during a marathon, without completely zapping your legs. Rather than spending the entire week recovering from the previous long run, you should be building a base for the forthcoming long effort.

For example, let’s take a look at the advanced marathon programme in Hansons marathon method. The programme includes a 16-mile Sunday long run. Leading up to the Sunday long run, the schedule calls for a tempo run on Thursday and easier short runs on Friday and Saturday. You don’t get a day completely off before a long run because recovery occurs on the easy running days. Since no single workout has totally diminished your energy stores and left your legs feeling wrecked, you’ll instead feel the effects of fatigue accumulating over time.

The plan allows for partial recovery, but it is designed to keep you from feeling completely fresh going into a long run. Following the Sunday long run, you will have an easy day of running on Monday and a strength workout Tuesday. This may initially appear to be too much, but because your long run’s pace and mileage are tailored to your ability and experience, less recovery is necessary.

The Hansons marathon method long run guidelines are based both on years of experience and on the research by Dr Jack Daniels, Dr Dave Martin, Dr Joe Vigil, Tim Noakes, and Dr David Costill. Instead of risking diminishing returns and prescribing an arbitrary 20-mile run, the Hansons marathon method looks at percentage of mileage and total time spent running. While 16 miles is often the suggested maximum run, we are more concerned with determining your long run based on your weekly total mileage and your pace.

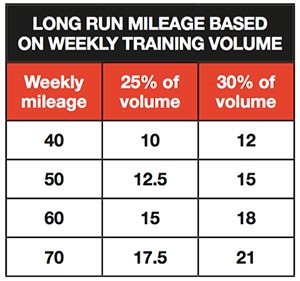

The Hansons marathon method will call for a long run that does not exceed 25-30% of your weekly mileage. Breaking this cardinal rule risks too much: injury, overtraining, depleted muscle glycogen, and subpar workouts in the following days or even weeks.

Yet a typical beginner marathon training programme might peak at 40–50 miles per week and then recommend a 20-mile long run. Although this epic journey is usually sandwiched between an easy day and a rest day, there is no getting around the fact that it accounts for around 50% of the runner’s weekly mileage.

It may sound unconventional, but you’ll find that the Hansons marathon method long run is firmly based in science with proven results.

Risks of the 20-mile-plus long run:

Marathon training is a significant undertaking and should not be approached with randomness or bravado.

If you are a beginner or low-mileage runner, your long runs must be adjusted accordingly. What is right for an 80-mile-a-week runner is not right for one who puts in 40 miles a week.

A Hansons 16-mile long run might be too short or too long for you. Before we make a conclusion, we must also consider your running pace.

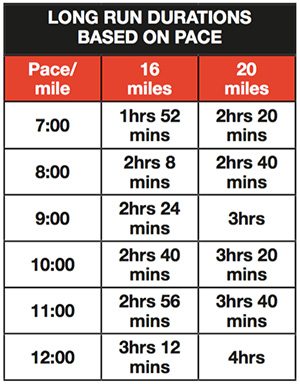

In addition to running the optimal number of miles on each long run, you must also adhere to a certain pace to get the most physiological benefit. Since we don’t all cover the same distance in the same amount of time, it makes sense to adjust a long run depending on how fast you’ll be traveling. The research tells us that 2:00–3:00 hours is the optimal window for development in terms of long runs. Beyond that, muscle breakdown begins to occur.

Look at the table above to see how long it takes to complete the 16 and 20-mile distances based on pace. The table demonstrates that a runner covering 16 miles at 7:00-minute pace will finish in just under 2:00 hours, while a runner travelling at an 11:00-minute pace will take nearly 3:00 hours to finish that same distance. It then becomes clear that anyone planning on running slower than a 9:00-minute pace should avoid the 20-mile trek.

This is where the Hansons 16-mile long run comes into play. Based on the mileage from the Hansons marathon programmes, the 16-mile long run fits the bill on both percentage of weekly mileage and long run total time.

So what does this mean for you? The science shows that a 20-mile long run might, in fact, be right for you, but only if your weekly mileage is around 65 miles per week and if your long run workout pace is faster than 9:00 minutes per mile.

Everyone else should consider the long run the Hansons way, by factoring in weekly mileage and pace.

» The Hansons Brooks Distance Project has helped develop elite runners. The Hansons Marathon Method by Luke Humphrey with Keith and Kevin Hanson, which is published by Velopress and widely available online, applies the methods for all standards