As athletes went about the business of winning medals at the IAAF World Championships this summer, sports scientists undertook a task of jaw-dropping magnitude in attempting to analyse the finer detail of their performances.

In an unprecedented study which was commissioned by the IAAF, Dr Athanassios Bissas, head of sports and exercise biomechanics, led a team of 40 scientists from the Carnegie School of Sport at Leeds Beckett University in detailing the technique and demands of 17 events.

It was a huge operation behind the scenes with the team using 40 cameras – comprising 25 high-speed cameras and 15 HD camcorders – and often working through the night to produce their results. For the first time, the scientists were also able to trial micro sized cameras fitted on the vests of some athletes who volunteered to participate in the trials.

Worn underneath the team kit, the lens peer out of a precise opening and does not impede performance.

Full results will take months to compile and will eventually be published on the IAAF website, but here we provide an insight into the preliminary findings from Dr Bissas’s studies, looking at the men’s 100m.

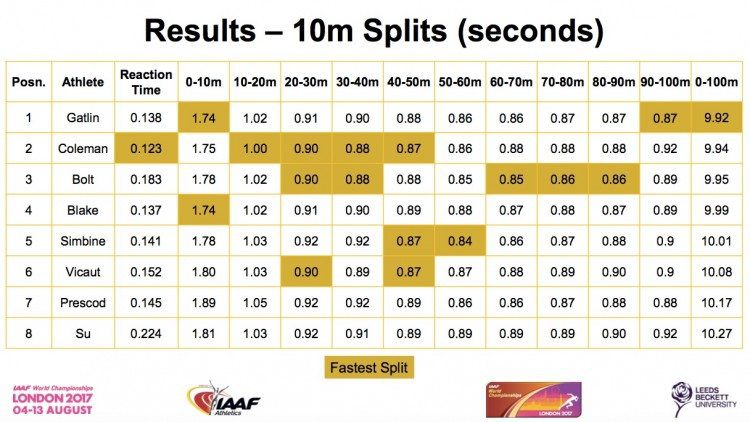

Eighteen high-speed digital video cameras were placed at multiple positions overlooking the home straight of the Olympic Stadium track to record 10m splits and 3D motion analysis data. The cameras recorded at between 100 and 250 frames per second with all the finalists filmed from a range of different angles.

Reaction time and performance in the very early stages of the race were shown to be clear key determinants. In contrast to the other medallists, the defending champion Usain Bolt’s reaction times increased through the rounds, when you would expect a decrease.

Yet his reaction time in the final was 0.045 seconds slower than Gatlin’s, which was more than the final time distance between them (0.03 seconds).

Previous studies, reported in Athletics Weekly magazine, have looked at Bolt’s asymmetrical running technique and this latest investigation also suggested anomalies in gait and spatial movement.

All three of the 100m medallists displayed some degree of asymmetry during the middle phase of the race, determined by differences in ground contact time. However, it was Bolt’s running that was the most significantly asymmetrical.

Overall, the top sprinters demonstrated consistent step length patterns suggesting that variations in stride frequency might explain fluctuations in performance.

To achieve high running speeds as athletes, the researchers noted that athletes “should place an emphasis on speed maintenance as slight reductions in speed towards the end of the race may equally determine the outcome of the race”.

They also stated that reaching high speeds in the middle and later phases of a 100m race won’t necessarily compensate for a slower start.

A comparison was made of Bolt’s London 2017 performance with his world record run in 2009 at the IAAF World Championships in Berlin, analysing both races over 20m splits. Not surprisingly, it showed that Bolt’s speed is lower throughout all stages of the race including the later stages in which he usually outperforms his rivals.

Distance - Berlin (2009) - London (2017)

20m - 2.89 - 2.98

40m - 4.64 - 4.76

60m - 6.31 - 6.49

80m - 9.58 - 9.95

Q. Are we seeing anything new in the 100m?

A. TCUP – Technical Control Under Pressure, something that applies in all closed skills like sprinting, just like shot or hammer. Get the body angles right at the start, and strong leg-extensions through the pick-up. Then flow loose and hold shape all the way to the tape with a timed dip.

Q. How did Great Britain’s Reece Prescod perform?

A. He performed very impressively. His clockings at 40m onwards were directly comparable with the medallists. Indeed, in his semi-final, he was pulling in the leaders in this section of the race.

Q. So what would be Prescod’s main area of improvement?

A. Start and pick-up. His reaction time is good, but he was weak out of the blocks, and his first 10-30m was poor, relative to the medallists. He appeared to be high on leg-speed, low on horizontal drive in that 0-40m phase.

Q. What was Usain Bolt’s race pattern?

A. The big surprise was that he tightened up in the face and shoulders in the final 10 metres, which is a point where he normally continues to surge away from the field. That may well have cost him the race.

Q. Any thoughts on the future of sprint training?

A. To return to the medium start, with drive from both legs. producing greater block-velocity. Also a more prudent, selective use of drills and quasi-therapeutic exercises.

Q. Can an athlete’s reaction time be trained?

A. Yes, certainly at the levels of difference displayed in the race. I see lots of coaches working on starting, but many use a voice- stimulus. I would always use a clapper board or a shrill whistle, and best of all, a starting-gun. Make it real. The Usain Bolt we saw in London was clearly rusty in all aspects of race fitness, but was always weak in this area.

Q. Your thoughts on British sprinting?

A. Very healthy. CJ Ujah is much better than the athlete we saw in London – he has shown that by his performances in the Diamond League. Prescod is outstanding. The relay squad’s exchanges were the best that I have ever seen from a British squad. I thought that Dina Asher-Smith’s 200m run was the best that I have ever seen from a British woman and was incredible under the circumstances.

Lessons learned Q&A by Tom McNab

» Other analysis in this review series can be found here