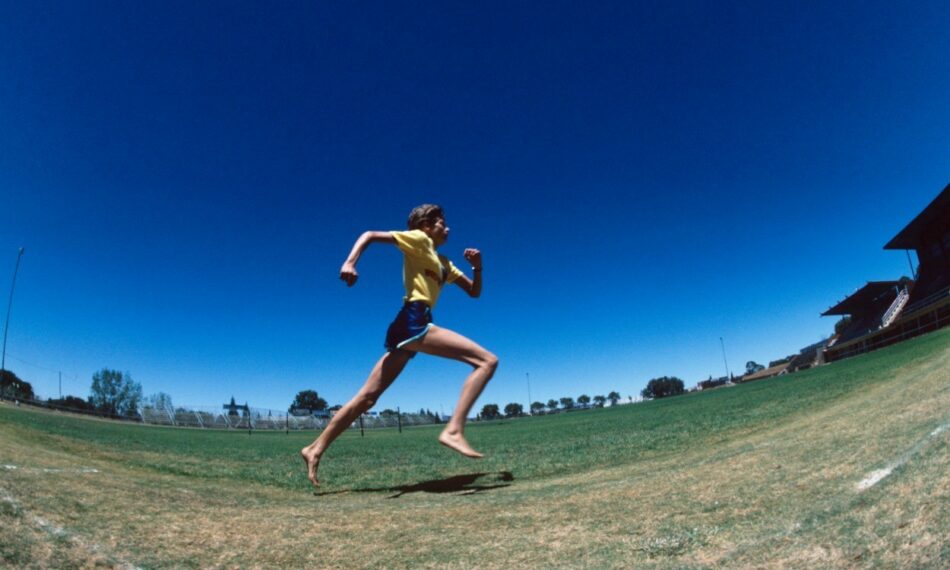

John Shepherd considers whether barefoot is the way to go

Over the last few years barefoot and minimalist shoe running has become very popular. In the distant past, top GB runners such as Bruce Tulloh, Ron Hill and Zola Budd discarded their shoes and the legendary Abebe Bikila went barefoot in the 1960 Olympic marathon and won! Nowadays many African runners tend to do their running miles to and from school unshod.

What the researchers say

A review of relevant studies up to January 2013 concluded that low methodological values made analysis of claims for and against barefoot running difficult to make.

However, the researchers discovered:

» Moderate evidence that barefoot running reduced peak ground forces (providing the runner landed on their forefoot, heel-striking is still possible), increased foot and ankle plantar flexion (toe-down foot position) and increased knee flexion (bend) on ground contact compared with running in neutral shoes (these adaptations are needed to reduce what the researchers call “ground collision forces”)

» Barefoot running required a shorter and faster stride rate

» On review of the weaknesses of the studies it was stated the “body of work is compromised by the lack of evaluation after habituation, or re-training, of previously shod rearfoot-striking runners to barefoot forefoot-striking running styles”. Obviously this would require a longitudinal study of a large magnitude and constant monitoring of adherence to the barefoot technique and whether the runner could get anywhere near matching the mileages they could when shod.

Benefits of barefoot running

1. Forefoot strike and reduced ground collision force

Barefoot running obviously creates different forces through your feet compared to running in shoes. Because of this the muscles and tendons of the lower leg have to do much more work and they do this differently. This typically results in a greater toe-down, forefoot action with increased knee bend when running barefoot to compensate for the need to absorb impact through the body’s structures.

There’s no thick, cushioned heel-strike area as is the case with many contemporary running shoes. The soleus and gastrocnemius muscles of the calf and the Achilles tendons will have to work particularly hard and eccentrically (when muscles lengthen under load), when barefoot. This occurs when the feet hit the ground and control has to be supplied to the downward motion of the foot and body as the heel drops. It’s therefore not that surprising that those new to barefoot and minimal shoe running may at least initially experience soreness and even lower-leg injuries.

Researchers from Harvard University discovered that after controlling stride for stride frequency and mass that barefoot or minimal shoe runners were 2.4% more efficient when forefoot striking compared to shod runners. The researchers put this down to a greater elastic energy return.

2. Barefoot running increases stride frequency

A consensus in the research holds that barefoot running requires a faster cadence and reduced ground contact times. The barefoot running style involves a low knee lift and a quicker turnover, which reduces impact forces compared to the use of a longer stride length and slower stride rate (as would most likely be the case when running in shoes).

3. Effects on the foot arch

The arch of your foot has to work harder when running barefoot. It is an elastic yet very strong component of your foot and its structure dissipates force on landing and assists on push-off into each and every stride. The underside of the foot is made up of four layers of muscle tissue as well as a length of thick connective tissue called the plantar fascia, which supports the arch. If the surrounding muscles weaken, the plantar fascia will drop and the arch will collapse. This results in “flat feet” syndrome. In active people flat feet can lead to the feet rolling in too much (over pronation) and forces being fed around the body in a less than optimal way, which could lead to injuries.

Running and walking barefoot are often recommended as a “cure” for flat feet. However, the arch will need time to adjust to the needs of consistent barefoot or minimal shoe running.

Barefoot running and energy cost

It would seem that wearing nothing on your feet when running would save energy. Even the lightest of shoes have to be picked up on each stride over and over again as you travel along. However, what this commonsensical notion fails to account for is the specific energy cost of producing each and every stride in entirety across the body – known as “metabolic cost”.

Researchers from the University of Colorado considered metabolic cost and oxygen processing costs when analysing various running conditions (12 males with “substantial barefoot running experience” participated in the study).

The conditions were running:

(a) Barefoot (with mid-foot strike at 3.35m/sec)

(b) In lightweight shoes at the same speed (shoes weighed 150g per shoe)

(c) At the same speed with weight added by way of lead strips to the shoes (weight was increased by 150g, 300g and 450g per shoe)

(d) At the same speed with weight added by way of lead strips to the feet (weight was increased by 150g, 300g and 450g per foot)

The researchers found that running barefoot had a higher metabolic cost than running in shoes (plus 3-4%) and that the metabolic cost of running increased approximately by 1% for every 100g added per foot, whether barefoot or not. This led the researchers to conclude: “Running barefoot offers no metabolic advantage over running in lightweight, cushioned shoes.” Why would it be more energy demanding to run barefoot? Well, as indicated, the structures of the body have to work harder to control and produce energy – they can’t rely on shoes to do the job for them.

It would have been useful, however, if the research involved runners who had never run in shoes, as it is likely that their metabolic demands would be less affected (due to them, and more specifically, their bodies not having gained a familiarity in running in shoes, with all the absorbency that this offers). Conversely, it’s possible that the addition of the various shoe conditions would have upped the metabolic and oxygen costs of the always-barefoot runners, but research is needed in this area.

The Achilles tendon and footstrike variation

This band of soft tissue that connects the heel bone to the calf muscles is crucial for all locomotion and supplies a great deal of energy, due to its elastic recoil properties. Runners who have suffered from Achilles injuries will know only too well how important these relatively small bands of tissue are compared to, for example, the much larger glute muscles when it comes to running when they are injured and not functioning properly.

Barefoot running footstrike variations can place different strains on the Achilles and researchers from the University of Exeter considered these variations when habitually shod runners ran barefoot.

The runners used four conditions:

Heel-striking (HS)

Mid-foot striking (MS)

Forefoot striking (FS)

Toe-striking (TS)

It was discovered that TS and FS runners required greater leg stiffness. This would be necessary to control the specific forces generated by a landing technique that would involve greater dorsiflexion. The TS condition was identified as placing the greatest strain on the Achilles tendon. The researchers concluded: “These findings indicate the importance of considering foot-strike modality in research investigating barefoot running.”

Leg stiffness refers to the characteristics of the legs in terms of absorption and energy return on footstrike. Sprinting, which is a forefoot activity, and running under barefoot running conditions requires greater leg stiffness. This is due particularly in the case of the sprinter to the need to return energy quickly to maximise speed. The barefoot runner needs leg stiffness for similar reasons, although top speed is not their priority. If both these runners’ legs were overly flexed on landing from each and every stride, a great deal of energy would be lost and running efficiency compromised. In traditional running shoes, leg stiffness will be less of a requirement as the shoe absorbs much of the force and does much of your legs’ work for you. Indeed many shoes are designed to aid energy return.

Speciffic ground forces and bodyweight multiples

The Harvard researchers looked at the specific impact forces and the ground contact times of barefoot and shod running. They found, for example, that under barefoot conditions at the peak of ground contact that the runner in their survey was in contact with the ground for 0.206sec, while overcoming a bodyweight multiple of 2.45. This contact speed is more than 50% quicker at a similar point compared to the shod runner (0.532sec). However, it is interesting to note that the weight the runner absorbs on each footstrike is very similar (2.45 to 2.47 times bodyweight) whether barefoot or shod. This in part reflects the fact that the test was done with the same runner at the same running speed, but it should apply broadly to all runners used to running in shoes, who then remove them for comparison.

The shod runner therefore spends more time absorbing force on each stride. It’s this that is used by proponents of barefoot and minimal running shoes to vindicate that this method of running is better on a runner’s body.

What matters?

Researchers from Taiwan implied that it may actually be a red herring comparing barefoot and minimal shoe running with shod running and looking to see which is best. Instead, they imply that what may be more important is the way the runner’s feet contact the ground – forefoot or rear-foot – with or without shoes.

This is what their survey of 12 habitually shod runners who ran (a) barefoot with a forefoot strike, (b) barefoot with a heel-strike, (c) shod with a forefoot strike and (d) shod with a heel-strike came up with: “The results showed that the lower extremity can gain more compliance when running with a forefoot strike. Habitually shod runners can gain more shock absorption by changing the striking pattern to a forefoot strike when running with shoes and barefoot conditions. Habitually shod runners may be subject to injuries more easily when they run barefoot while maintaining their heel strike pattern.”

So, much of this is in accordance with the research previously quoted, but what is crucial is the fact that keeping shoes on and moving to a more forefoot strike may be a good interim or even long-term option to take. This is especially the case given the highly ponderable consideration of how long it would take a runner used to running in shoes to actually make the full-blown switch to running without them or in minimals. More research is needed on this. The right type of shoes may also be needed to allow for a forefoot strike as support shoes, for example, are not designed for a forefoot strike.

Is barefoot the way to go?

This is a very difficult question to answer. The research that exists is in its infancy and the conclusions that have been drawn are not clear-cut. Yes, impact forces are significantly reduced compared to running in shoes and heel-striking, but there’s a greater metabolic cost. However, it could be argued that running in shoes makes you a “lazy” runner and therefore less energy-efficient too.

There’s also a potentially greater risk of injury if you don’t progress your barefoot transition carefully and progressively, but the risk of injury also applies more to the consistent heel-striking shod runner. Your feet will need to toughen up and get used to no protection if you do go barefoot or minimal, but just like any new exercise, they will adapt to the new stimulus in time. You may also want to experiment with a forefoot running action as an alternative progression while shod. The bottom line is to tread wisely and very carefully if you wish to explore the barefoot or minimal shoe running path.

Four barefoot running tips

1. Don’t think you can simply kick-off your shoes and cover the same mileage as you did shod. This change in your running form requires muscles and tendons to adapt, which takes time. Rushing into it will almost certainly finish with injury.

2. Treat barefoot running as a totally new form of exercise. You may be asking your body to use muscles it has never used before for running. Your training should allow for these adaptations to take place slowly.

3. The soles of your feet will be over sensitive if you are not used to being barefoot. Before even thinking about running, start by getting used to moving around barefoot over different surfaces and build this up gradually.

4. Although running barefoot is the best way to learn proper technique, there is also benefit to wearing a little protection from the elements by using a barefoot shoe that allows your foot to work naturally. Many transition shoes will still over-protect your feet, support your arch, lift your heel and squash your toes together, limiting their movement.

» Tips are provided by Paul Mumford, a barefoot running expert

» John Shepherd is the editor of ultra-FIT magazine and the coach to European junior long jump champion Elliot Safo. He is the author of various books, including most recently Strength Training for Runners , published by A&C Black.